Generations of Christian worshipers, and even atheist historians, have admired the Apostle Paul, for his consistent philosophical advice, his remarkable writing skill, and of course his willingness to undergo imprisonment, torture, and death for his views. Yet writers frequently lament the fact that people admire him, while paying little attention to his teachings.

That is a consistent theme throughout history. In more modern times, think of the decades Ghandi spent leading the Hindu Nationalist movement in India, and teaching the effectiveness of non-violence, only to be gunned down by a fellow Hindu nationalist. Or the irony of Americans making Martin Luther King’s birthday a national holiday, while ignoring his preaching about treating all people equally. I think it is also true of the great leaders of the conservation movement, people we honor – as long as we don’t have to spend time studying them.

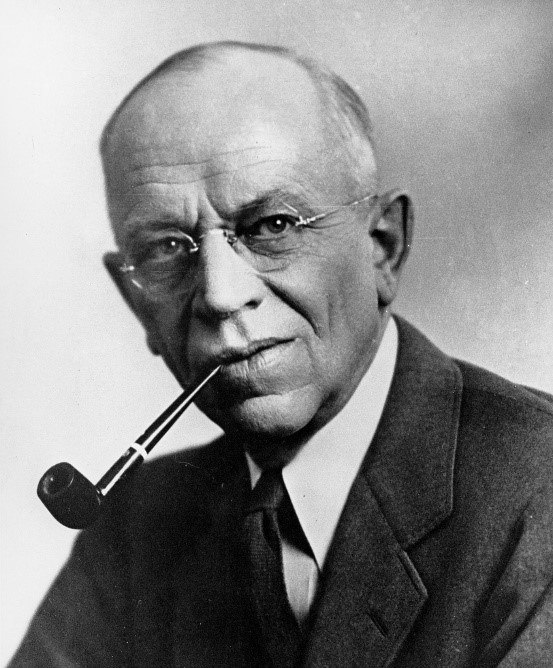

For me, the perfect example is Aldo Leopold, often called the father of wildlife ecology. At first glance, this may seem like obscure history. You might wonder if I finally got to the end of the internet, and this was the last thing on it. But our system of protecting wildlife, which most of us care about, would have evolved very differently had Aldo Leopold not died prematurely.

During Leopold’s heyday, the New Deal era, a new aspect of the environment began to creep into the American consciousness: wildlife ecology. This idea went far beyond earlier concepts confined to game management, to a much broader vision, an understanding that all wildlife is interdependent, coexisting in a “circle of life.” Previously, conservationists and governments had concentrated on protecting game from extinction. The Boone and Crockett Club was founded specifically to ensure there would always be game and fish. But this was a broader understanding of the connectedness of wildlife, including predators, rodents and insects, even the ugly critters no one wanted to hunt or eat. Leopold’s first book, in 1933, was about managing and restoring wildlife populations. He argued that species must be protected from extinction not just because we need food, but because they have an intrinsic value of their own.

Leopold was a renowned scientist and scholar, an exceptional teacher, and a gifted writer. A Yale-trained forester, he spent 19 years with the U.S. Forest Service. In 1928 he quit to become an independent contractor, primarily conducting wildlife game surveys. He became a Professor of Game Management in Wisconsin, teaching there the rest of his life. But his legacy came from his brilliant writing.

Lots of professors write books, but few have the profound influence of Aldo Leopold. He wrote several, the best known being A Sand County Almanac, published after his death and read by millions. He combined a nearly poetic style with scientific observations of nature, and commentary on protecting and preserving the most vital natural resource, the land. Leopold’s essays led to the modern understanding of living in harmony with the land – especially with wildlife. He viewed the land as a living organism and wrote of “the whole community of nature,” leading to a new science intertwining forestry, agriculture, biology, zoology, and education.

Leopold was internationally respected, and was instrumental in formulating policy, promoting wilderness, and building ecological foundations for forestry and wildlife protection. He died of a heart attack while helping a friend put out a brush fire on a neighboring farm in 1948. But his legacy has grown stronger over the years and every serious student of conservation has a worn copy of A Sand County Almanac.

One of his famous essays was on “Conservation Economics,” warning of “the time-honored supposition that conservation is profitable.” His carefully reasoned ideas about private land that is also important habitat bear repeating, because the vast majority of wildlife habitat is on private land. He concluded that conservation only becomes possible on private lands when it also becomes profitable for the landowners. In 1934 he wrote simply “that conservation will ultimately boil down to rewarding the private landowner who conserves the public interest.”

What if landowners were paid to create and preserve habitat, or better yet, to raise endangered species as efficiently as they raise livestock? Those would be powerful incentives for recovery of hundreds of endangered species. Some people might make money, by providing a service the rest of us want. Our punitive regulatory system seems to think self-interest is morally wrong. That thinking has proven to be bad for wildlife. Aldo Leopold knew that. Instead of merely admiring him, we ought to read him.

Comments on this entry are closed.