Comics used to joke, “Maybe we’ll see things more clearly by 2020.” After a string of jokes about how muddled and confused the world seemed, the reference to perfect vision sounded especially humorous. It has only been 2020 for three days, but there are already hundreds of columns, editorials, and books using the now-trite reference to better vision.

Self-criticism is part of human nature, leading to a desire for constant change, an unending effort to create utopia. People tend to believe every bad situation can be fixed, and after every tragedy they vow to make sure it never happens again. Thus, we never think things are good enough (they aren’t), so we tend to forget how far civilization has advanced. Our politics are filled with contempt, and the divisiveness seems worse than ever (it isn’t).

Self-criticism is part of human nature, leading to a desire for constant change, an unending effort to create utopia. People tend to believe every bad situation can be fixed, and after every tragedy they vow to make sure it never happens again. Thus, we never think things are good enough (they aren’t), so we tend to forget how far civilization has advanced. Our politics are filled with contempt, and the divisiveness seems worse than ever (it isn’t).

Perhaps in 2020, our attempt to see things more clearly will encourage a broader perspective, and a little pride. Matt Ridley, author of “The Rational Optimist,” just published an important column in The Spectator outlining the greatest decade in human history – this one. He points out the phenomenal progress of mankind in reducing extreme poverty to less than 10 percent for the first time (it was 60 percent when he was born in 1958).

He points out that African and Asian economies are growing faster than those in Europe and North America, child mortality is at record low levels, famine is virtually nonexistent, and malaria, polio and heart disease are declining. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of human progress, though, runs counter to all the doomsday warnings. Namely, our civilization is growing while using less natural resources, not more.

Andrew McAfee of MIT, author of “More from Less,” documents several nations now using less metal, water, and land, while their economies are growing. In Great Britain, the quantity of all resources consumed per person, including biomass, metals, minerals and fossil fuels, fell by a third in the last two decades, while the population and economy grew.

Ridley uses cell phones as an example, because with a small quantity of resources, they replace not only telephones, utility poles and wires, but also cameras, radios, flashlights, compasses, maps, calendars, watches, newspapers, and even card decks. Incandescent light bulbs once used four times more energy than LEDs, and modern offices use less paper than ever. Buildings contain less steel, and many construction materials now come from recycled products.

Most intriguing is the progress of modern agriculture. The same volume of food is produced on roughly 35 percent of the land it took 50 years ago, resulting in better supplies of more affordable food for much of the world. And agriculture’s shrinking footprint has other less-apparent benefits. Forests are expanding, not shrinking, in most of the wealthier countries, including the U.S., where there are more trees today than when Columbus arrived in 1492. That also aids in the recovery of major wildlife species, including wolves, deer, moose, beavers, lynx, seals, otters, bald eagles, and polar bears – all of which were once in grave danger but are now increasing.

The efficiency trend is especially important for water. Worldwide increases in water use are considerably smaller than once predicted, as Ridley points out. “Experts in the 1970s forecast how much water the world would consume in the year 2000. In fact, the total usage that year was half as much as predicted,” he writes. “Not because there were fewer humans, but because human inventiveness allowed more efficient irrigation for agriculture, the biggest user of water.”

That is an almost unimaginable achievement, that more, better, and cheaper food can be produced from less land, using less water, than in our grandparents’ generation. The age-old open-furrow irrigation system has given way to concrete ditches, drip systems, and micro-jet sprinklers, saving water while reducing the growth of weeds and the need for herbicides. And available, affordable energy has brought a higher standard of living to billions.

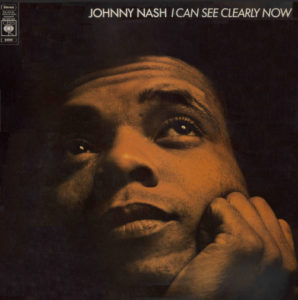

Obviously we still face difficult problems, and the challenges of our age are as real and exciting as any other time in history. The great singer-songwriter Johnny Nash created a beautiful mental picture in his 1972 hit, “I Can See Clearly Now.” He wrote, “Look all around, there’s nothing but blue skies.” The real world may not be quite that rosy; maybe we can’t completely agree that “All of the bad feelings have disappeared.” But perspective is important, and historically speaking, it is in fact “a bright, bright, sunshiny day.”

It’s 2020. Shouldn’t our vision be a little better?

An edited version of this column appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel January 3, 2020.

Comments on this entry are closed.