The National Wildlife Refuge System began modestly in 1903, but today it is the largest wildlife conservation program in the world. It includes 562 refuges, totaling over 150 million acres, in all 50 states and numerous islands from the Caribbean to the South Pacific.

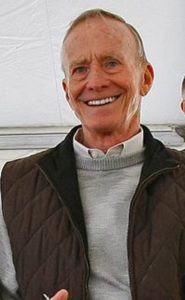

That system just grew a bit more, thanks to a wealthy patron donating 6,200 acres adjoining the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge in the Florida panhandle. Sam Shine spent years buying old tree farms there, harvesting the commercial trees, replanting native longleaf pines, and consolidating his holdings. He is well known in the region, thanks to his support of an even larger acquisition by the Nature Conservancy, the 17,000-acre Flint Rock Wildlife Management Area.

That system just grew a bit more, thanks to a wealthy patron donating 6,200 acres adjoining the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge in the Florida panhandle. Sam Shine spent years buying old tree farms there, harvesting the commercial trees, replanting native longleaf pines, and consolidating his holdings. He is well known in the region, thanks to his support of an even larger acquisition by the Nature Conservancy, the 17,000-acre Flint Rock Wildlife Management Area.

The Shine donation may seem small compared to the total federal holdings there. Its addition will help connect a 100-mile long conservation corridor along the Big Bend coast. St. Marks now encompasses over 80,000 acres spread over Wakulla, Jefferson, and Taylor counties, including coastal marshes, islands, tidal creeks, seven rivers, and former pine plantations that once supported a thriving lumber economy.

St. Marks is adjacent to the Apalachicola National Forest, Apalachicola River Wildlife Area, four huge “Wildlife Management Areas” called Flint Rock, Box R, Aucilla, and Big Bend, as well as Tate’s Hell State Forest, and Econfina and Ball River State Parks, making virtually that entire coastal area government property. If the donated 6,200 acres seems small, consider the excitement of the federal regional manager: “This is the single most important acquisition I’ve witnessed in my seven-and-a-half years as regional chief, and one of the biggest I’ve seen in 26 years in the Southeast region,” he said, calling it “a crown jewel in our system.”

Sam Shine is a great success story, an Indiana farm boy who started manufacturing electronic cables and connectors in 1976, in two rented rooms behind an insurance agency. He grew it into a $713 million manufacturing empire with factories and offices in Indiana, Asia, Europe and Latin America. His foundation has supported conservation projects in Indiana and Florida for 25 years, and his dedication to preserving Florida’s gulf coast deserves the accolades.

Still, even a great conservation-minded philanthropist like Mr. Shine has trouble imagining how to preserve great places without government ownership. He told one interviewer, “I’ve held this ground for 10 years and I was hoping that the Fish and Wildlife Service would buy it all, but obviously it was going to take more than my lifetime, so I decided, ‘Well there’s no point in continuing to pay taxes and insurance and all the things it takes to manage the property, so I’m just going to give it to them.”

Beyond the expenses, though, he seems to believe private owners are ruining the place, despite his own powerful example to the contrary. “We’re doing damage to the land and to the planet and it’s important to me to do whatever I can to reverse the damage.” His big-picture view is even more revealing: “I’d like to take the whole Southeast – the whole country – and put it back to the way it was in pre-white man days,” he told one reporter. “It was a wonderful country then and we crapped it up over the centuries.”

But in fact, he was not damaging the land. He and other donors – not the government – paid to restore the native vegetation and preserve important habitat. There are thousands of examples across America of private landowners doing remarkable conservation work, but their efforts are seldom publicized. Maybe that’s because so many, like Mr. Shine, are modest and do not seek public adoration. But there is another reason we seldom notice.

We are thoroughly conditioned by decades of experience with efforts to acquire such special places, to make them national parks, forests, wildlife refuges, national seashores, conservation areas, or wilderness areas. Perhaps we simply can no longer think outside the confines of government ownership.

The St. Marks refuge manager said, “Since it joins our property, we now own all the land from the gulf up to the coastal highway. So that’s pretty cool.” But is it?

National Wildlife Refuges are subject to the whim of congressional appropriations, their funding always uncertain. More to the point, there isn’t enough money in the entire treasury to buy all the beautiful and important places in this country. Maybe it’s time to re-examine how we go about conservation, perhaps rewarding owners with incentives for sound management – rather than thinking the taxpayers have to own everything we value.

This column first appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel June 21, 2019.

Comments on this entry are closed.