Would you invest in a business with a debt it could never hope to repay? If you knew the largest company in the world was about to face hundreds of billions in fines, would you still buy its stock? Would you invest in municipal bonds in a city you knew would no longer exist in 20 years because of a natural disaster? Any savvy investor would pass. That’s why these scenarios are at the heart of today’s most intriguing legal battle.

On the surface, these lawsuits are about global warming, perhaps the future of life itself. But like so many of today’s natural resources disputes, they are really about money. And these cases could change the political world as dramatically as mankind is said to be changing the natural one.

It began with an accusation against big oil companies, by a number of state and local governments, claiming big oil knew about climate change years ago, knew their industry was causing it, knew it could destroy life on Earth, and purposely hid those facts from investors. Several liberal State Attorneys General pursued such charges against Exxon and others, using the same organized-crime racketeering law that slew big tobacco 20 years ago.

Such use of the racketeering law was unprecedented then, because it was outside the law’s original anti-mob purpose. But the government’s case claimed tobacco companies had engaged in a decades-long conspiracy to mislead the public about the risks of smoking. The strategy worked, resulting in $200 billion in fines, bankrupting all the small and medium companies, and leading to smoking bans across the country. What a boon to the environmental industry if they could similarly kill off big oil!

Mind you, there is a vast difference between the tobacco and oil cases. The tobacco industry supposedly conspired for 50 years to hide something we all know, that smoking is harmful. Climate change is far less settled in public opinion. Many Americans remain unconvinced of a relationship between cars and weather. Voluminous research, on both sides of the issue, is still underway. The Obama Administration was completely convinced; the Trump Administration apparently less so. Perhaps that illustrates that the public remains divided. Still, the prospect of hundreds of billions of dollars is too good to pass up, for environmental lawyers, and for many in government.

Several California cities have filed lawsuits, supported by huge internationally-funded environmental law firms. The City of Boulder has joined in, its council arguing that the city has had to spend money to address climate change issues partially caused by emissions from fossil fuel producers. It doesn’t specify exactly how rising sea levels would impact a city 5,430 feet above sea level, or how that has cost the city extra money. They are just betting on a mass of lawsuits being settled with fat checks, and want to get in on it early.

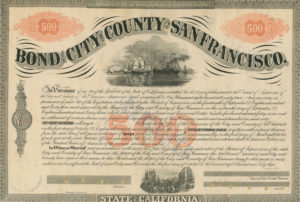

There is a problem with this accusation, though, which cities are just realizing. Speculation about the climate works both ways. Oil companies depend upon investors investing. But so do local governments. Most, including Boulder, depend on municipal bonds to fund infrastructure, including highways, bridges, and schools. Municipal bonds attract investors because they are tax-exempt, and fairly safe. Investors consider risks like fluctuating prices, reliability of city revenue, or inflation eroding the value. But what about the risk that a city might not even exist in a few years, the victim of catastrophic rises in sea level due to global warming? Many cities claim to face such an ominous future, yet no city warns bond investors about it.

That is the gist of an Exxon lawsuit against the California cities pushing these racketeering cases. San Francisco, for example, claims it faces “imminent threat of catastrophic storm surge flooding” caused by global warming. A Berkley study says San Francisco is even more vulnerable to sea level rise than previously thought, because the city is sinking. Sea level rises, combined with subsiding land, could inundate 165 square miles, obliterating the City. This study is cited in San Francisco’s lawsuit against Exxon, but are its municipal bond investors warned that the city may not exist in a few years? Of course not. So, are city officials guilty of the same kind of conspiracy of which they accuse Exxon, trying to hide truth from their investors?

That is the gist of an Exxon lawsuit against the California cities pushing these racketeering cases. San Francisco, for example, claims it faces “imminent threat of catastrophic storm surge flooding” caused by global warming. A Berkley study says San Francisco is even more vulnerable to sea level rise than previously thought, because the city is sinking. Sea level rises, combined with subsiding land, could inundate 165 square miles, obliterating the City. This study is cited in San Francisco’s lawsuit against Exxon, but are its municipal bond investors warned that the city may not exist in a few years? Of course not. So, are city officials guilty of the same kind of conspiracy of which they accuse Exxon, trying to hide truth from their investors?

Talk about hypocrisy. Politicians predict dire calamities when advocating carbon taxes, fracking bans, and massive fines. But when selling bonds to finance future construction, they assure investors, “forget that, everything will be just fine.”

A version of this column originally appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel April 20, 2018.

Comments on this entry are closed.