I am willing to bet that you have never heard of Executive Order 13497. There is no reason you should have, except that it is enormously important to the process of governing America. The simple reason most people never heard about it is that President Obama signed it less than a week after his inauguration.

The details are complicated, but it has to do with the way federal agencies make rules. That’s more interesting than usual now, because Americans feeling overburdened by federal regulation just elected a President who promised to scale back such regulatory overreach. Previous Presidents have addressed this issue, too, hence the Executive Order in question.

President Ford was sensitive to the impact of regulations on the economy, so he issued an Executive Order requiring “inflation impact statements” with all new federal rules. President Carter changed that, requiring agencies to more broadly consider potential economic impacts and identify alternatives. President Reagan repealed Carter’s order and instead directed agencies to implement rules ONLY if “potential benefits to society for the regulation outweigh the potential costs to society.” President Clinton revoked most of that requirement, subordinating the cost-benefit analysis to the agency’s law enforcement “duty.” President George W. Bush reinstated the Reagan requirement, and also directed all departments to create an Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, and to report the cost-benefit analysis. Predictably, with Executive Order 13497, President Obama revoked it and reinstated the earlier Clinton order.

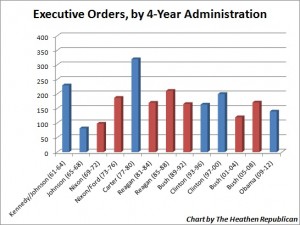

The use of such ministerial power may reveal much about a President’s ability to work with Congress. That might explain why some Presidents issued very few, whereas Woodrow Wilson used Executive Orders 1800 times and FDR over 3500. Obama has actually signed fewer Executive Orders per year than many Presidents, but it isn’t the number of orders that rankles so many political leaders these days. It is the feeling that executive power is usurping legislative power, bypassing the process, violating the rule of law.

The use of such ministerial power may reveal much about a President’s ability to work with Congress. That might explain why some Presidents issued very few, whereas Woodrow Wilson used Executive Orders 1800 times and FDR over 3500. Obama has actually signed fewer Executive Orders per year than many Presidents, but it isn’t the number of orders that rankles so many political leaders these days. It is the feeling that executive power is usurping legislative power, bypassing the process, violating the rule of law.

This is not partisan, and it is not new. Many presidents have faced this same criticism, especially when their directives implement programs that Congress opposes. Presidents often figure there is more than one way to skin the cat, so they do what they think they must. Thus, an executive order is one of many tools available to Presidents to further their policy goals. However, such orders are inherently unstable, because any President can revoke, modify, or supersede his own orders – or those of a predecessor. Today lots of folks are hoping the incoming President will repeal a number of orders issued by the outgoing President. Outgoing Presidents know that, so some have loaded the most controversial policies into last-minute orders.

Clinton created vast national monuments that he could never get Congress to approve because the people who lived there were opposed. Obama has done the same, in Utah and Nevada, and is likely to do more, as well as release most prisoners from Guantanamo, create new advisory committees and federal offices, and issue policy guidelines on a range of issues.

Here is the problem. Every Executive Order, like every law and every program, has a constituency. Lots of people will be upset at any repeal, and will complain loudly that the new leader lacks compassion, favors special interests, hates the environment, is turning back progress, or whatever. Sometimes these firestorms can be difficult to overcome – not legally, but politically.

That is why repealing these actions taken in the last few weeks is more complicated than it seems. That requires two careful strategies. The first is to repeal them all, no picking and choosing. That way, no explanation is needed but this one: “I am against eleventh-hour government that short-circuits our public process, so I repealed every order issued within the last couple months, even knowing some of them may be needed. If so, those will make their way back to my desk in due course and be re-issued, the right way.”

The second strategy is almost as important. It should be done on inauguration day or shortly after. That gives opponents very little time to attract press attention, because the media is so focused on the inaugural parade (Will he get out and walk?), and the inaugural balls (what is she wearing?), and the special events (Which bands will play?). The pomp and ceremony is irresistible to the media, leaving major stories about important issues to the back pages. As is all too common in modern America, the legality is easier than the politics. But it can be done.

A version of this column originally appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel January 13, 2017.

Comments on this entry are closed.