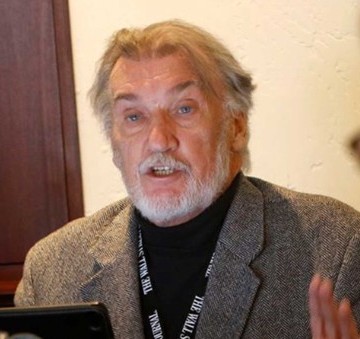

A friend named Stephen Heins is an energy and environment consultant who for a long time called himself “The Practical Environmentalist.” We’ve been kindred spirits for years because we never bought the conventional wisdom that a healthy environment is incompatible with a prosperous economy. We think the two concepts should not only be compatible, but complimentary.

Stephen now calls himself an “energy humanist,” referring to a growing academic discipline that seeks to reconcile humanity’s need for energy with its desire to protect the natural world. It differs from much of today’s environmental scholarship and activism because it focuses on improving the lives of people, especially the estimated four billion without access to affordable energy. It is a philosophy that does not view the environment as more important than people, nor people as an inevitable threat to nature.

The idea is consistent with everything I have always believed, and I like everything about this direction. Yet the association nevertheless makes me nervous. That’s because even in such a limited core group of new thinkers, there are very different understandings of what it means.

A handful of academics claim to have invented the concept of “Energy Humanities,” and consider themselves the original energy humanists. Primarily that’s based on publication of a book by that name, an anthology of essays complied and edited by Imre Szeman, a “cultural studies” researcher at the University of Alberta who coauthored “After Oil,” a full-throated damnation of “petroculture” calling for an end to fossil fuels; and by Dominic Boyer, a cultural anthropologist who sits on the board of Rice University’s Sustainability Institute and designed a memorial to the dying glaciers. Publicity for the book says, “The authors offer compelling possibilities for finding our way beyond our current energy dependencies toward a sustainable future.”

Nothing about that is new. Nothing about that is different than the diatribe we have heard for most of our adult lives, about how our pursuit of the good life is destroying the environment, if not the planet itself, and the only solution is for people to stop producing, manufacturing, and especially consuming. That is not humanism; it is junk science. It is a political agenda based on tearing down, not building up, and it most certainly is not about improving the lives of people who live in energy poverty.

That is not what Stephen Heins is writing about, nor what I believe, so my pitch is to stop giving credit to a handful of professors who contributed to Szeman’s book, to stop calling them the founders of energy humanism. In fact, they can be more accurately said to have hijacked an interesting and exciting new concept to push tired and discredited old nonsense. I rather commend Heins’s approach to some of life’s greatest challenges. He calls it “progress with a conscience.”

To me that has a fairly simple meaning. The great American conservation ethic founded in the era of Theodore Roosevelt has at its core two central missions. First, our abundant natural resources should be used to create the most prosperous society ever known, and second, that they should be used in a manner that is responsible and sustainable so they will still be available to future generations. That isn’t complicated, but the first half of it has been largely forgotten by today’s environmental industry.

Heins writes that “Energy humanism starts with a simple premise: energy is not an end, but a vital means.” He contrasts the two prevailing extremes: an obsession with limitless growth, which can trample communities and ecosystems, and “the ascetic environmentalism that sometimes romanticizes scarcity, ignoring the real needs of billions.” He wants a “middle path, demanding that energy systems prioritize people – especially the vulnerable – while respecting our environmental limits.”

That is a very stark contrast indeed with today’s environmental movement, and most government environmental actions, which not only fail to prioritize the needs of people, but generally view people as the enemy. It laments that Americans consume 12,000 kilowatts annually compared to 300 kilowatts in Ethiopia, as if Americans should strive to be more like Ethiopians. Heins’s version of energy humanism doesn’t seek to tear down the successful but to focus instead on “universal access to clean, reliable power” as “a moral imperative, not a luxury.” That can touch something deeper: our relationships not only with nature, but with each other.

That approach would shift the entire emphasis to solving real environmental problems, rather than pushing phony political agendas. It would be a long-overdue breath of fresh air.

{ 0 comments… add one now }