The U.S. government paid $55 million for the entire West. That’s less than a sixth of the annual budget of Grand Junction. In five separate treaties, the U.S. acquired the whole country from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase cost $23.2 million for all or parts of 14 states. In 1848, Mexico was paid $15 million, for Arizona, New Mexico, California, Nevada, Utah and Western Colorado. The $10 million Gadsden Purchase bought the land south of the Gila River, and Russia was paid $7.2 million for Alaska. In two other treaties, the U.S. acquired Minnesota, North Dakota, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Western Montana, without spending a cent.

Expanding the nation to the Pacific Ocean became an 1840s rallying cry, “manifest destiny.” But what did the U.S. government plan to do with all that land?

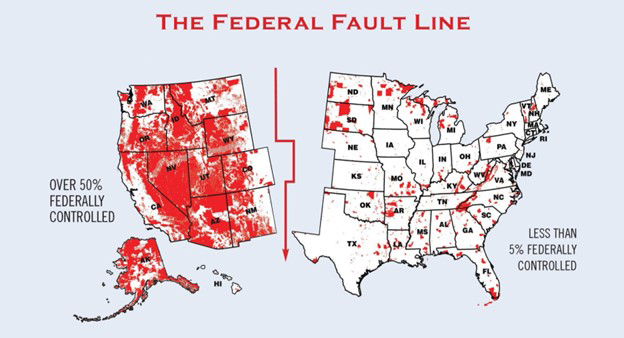

That is the subject of one of today’s most fascinating legal cases, the just-filed Utah v. U.S. Utah demands that the federal government turn over to the State all remaining “unappropriated” federal lands, that is, lands not designated by Congress as national forests, parks, monuments, wilderness areas, defense installations, or tribal lands. In other words, the 18.5 million acres managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

The history of federal lands is at the heart of it. Owning so much of the continent was a different matter than occupying it. So, the government’s purpose for the rest of the 19th Century was to convince Americans to settle this land, own and occupy it, and turn it into new states. It was viewed as crucial to future prosperity, hence Horace Greeley’s famous advice, “Go West, young man.” To encourage settlement of the West, the government sold these lands cheaply, and later even gave it away to homesteaders, railroads and states.

Utah’s suit argues that as new states were formed, the “disposal” of the federal lands was not only expected but required. Under the Constitution’s Article 4 “Property Clause,” Congress was given power “to dispose of and make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory or other property belonging to the United States.” The only specific exception, Article 1’s “enclave clause,” allowed permanent federal ownership of a ten-mile square district for the seat of government (D.C.) and for “forts, arsenals, dockyards and other needful buildings,” all requiring consent of the state involved. That condition, according to records of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, satisfied objections that unless the federal government’s ability to buy land required state consent, it would empower the federal government “to enslave any particular State by buying up its territory, and that the strongholds proposed would be a means of awing the State into an undue obedience.”

The contrary argument is the “elastic clause” granting Congress broad power “To make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers.” Utah uses that to argue that lands held permanently must therefore either be designed by Congress to be used for some enumerated power, or be held with consent of the State. Utah officially withdrew that consent and asked for transfer of the “unappropriated” federal lands more than a decade ago, citing similar transfers at the time of statehood to states east of the Rockies, and the Constitutional requirement that all new states be admitted on an equal footing.

All government programs to “dispose” of these lands officially ended with the 1976 Federal Land Policy Management Act (FLPMA), which governs the BLM. It left no doubt of Congressional intent: “The Congress declares that it is the policy of the United States that the public lands be retained in Federal ownership, unless as a result of the land use planning procedure provided for in this Act, it is determined that disposal of a particular parcel will serve the national interest.”

Utah’s suit asks the Supreme Court to rule this section of FLPMA unconstitutional and determine that the government was obligated to dispossess itself of BLM lands, absent some contrary Act of Congress, when the State asked it to do so in 2012.

Legal research on this complex and controversial issue has been underway for years across the West. Right or wrong, I can’t imagine the high court forcing “disposal” of all the BLM land in the West, if only for practical and political reasons – from which the justices are not immune. But if this case leads to new discussions about how these lands are managed, and the role states should play, it may prove nonetheless useful.

Comments on this entry are closed.