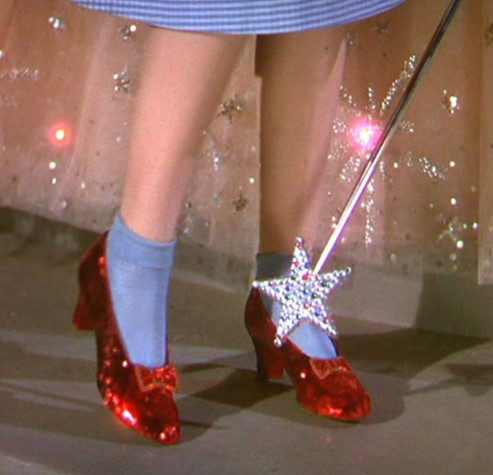

At the end of the classic, “The Wizard of Oz,” when Dorothy asks Glinda for help getting home, the good witch of the north says, “You don’t need to be helped any longer. You’ve always had the power.”

This week I participated in the Colorado Energy Summit in Montrose. Experts made presentations on diverse issues including oil, gas, geothermal, hydropower, nuclear, wind, solar, transportation and climate. I was struck by several examples of long-term debates about seemingly impossible problems, to which we have actually had solutions all along.

A great example is the most intractable problem with renewable energy, especially wind and solar power. That is, their reliability. Because the wind doesn’t always blow and the sun doesn’t always shine, the ability to store that power is essential. Without storage, reliability can only be addressed by continuing to operate coal and natural gas power plants. That could change if we had better technology for storage – not the batteries used in home installations, but on a massive utility scale. That’s always been the challenge for renewables.

Battery technology is slowly improving but cannot yet store enough electricity for large cities and entire regions of the country. But what if giant warehouses full of batteries were not needed? In fact, we’ve had much larger and absolutely reliable batteries for decades – if you consider an apparently unrelated technology – hydroelectric dams.

The solution is known as “pumped storage” or sometimes “storage and pump-back,” and has been around for generations, albeit for different purposes. We’ve always known pumped storage can improve the economics of hydro-electric dams. Electricity costs more when demand is higher, so the grid experiences peak demand in the daytime and lower demand at night. In this system, water is run through generators during peak daytime hours when the power sells at a higher price, then pumped back up to the reservoir during the night when power is cheaper.

There are lots of commercial pumped storage systems in the US, including big ones like the Taum Sauk plant in Missouri, Bath County in Virginia, Raccoon Mountain in Tennessee, and many smaller versions. That same technology is now being considered as a way, not just to generate electricity more efficiently, but to turn existing dams into giant batteries for solar and wind power storage, even at the nation’s largest reservoir, Lake Mead. It isn’t complicated – it simply uses solar and wind power to operate the pumps.

That’s the biggest pump-back proposal to date, to build a wind and solar-powered pump station 20 miles below Hoover Dam, to pump water back up to Lake Mead. Water stored in the lake would be released for power on demand, effectively turning the dam itself into the battery for solar and wind power. No new technology needed; the dam is already there.

Pumped storage projects can be constrained by geology, but more often by the federal permitting process, which can take decades. Dams are always controversial because of their environmental impacts. But with already-existing dams, these issues were long since argued, litigated, and resolved.

The potential is enormous. There are 1,756 hydroelectric facilities in the U.S. and another 80,000 unpowered dams, many of which could still have turbines installed. Turbines were installed at Ridgway Reservoir years after its completion and have been added to existing facilities like the South Canal in Montrose for years.

Hydropower is in fact the most reliable source of energy imaginable. The 50 oldest electric plants in the U.S. are all hydroelectric generators, all of them over 100 years old. In Colorado, 60 hydroelectric plants generate over 1.5 million megawatt hours annually, a fourth of it from the three dams at the Aspinall Unit. New facilities like that are expensive to install, but far cheaper to maintain and longer-lasting than any other energy source.

Pump-back projects already exist at Cabin Creek near Georgetown, and are planned in several other places including the Yampa River Valley, and another in Fremont County. A developer there says, “Once built and operating, the maintenance costs are very, very low, and the system will last, if properly maintained, a century or longer… when you run the financial models over 30, 50 or 60 years, this technology is, hands down, the cheapest technology on the market for [energy] storage.”

That’s why a pumped-storage project on the south slope of Pikes Peak is being called “essentially a giant battery for energy storage.” Maybe the good witch is telling us we’ve always had the power to solve renewable energy’s biggest problem.

Comments on this entry are closed.