The Dutch electronic band Quadrophonia had a minor hit in the 1980s called “Wave of the Future,” hardly an original title. It was the name of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s 1940 book calling for appeasement with Hitler. Various magazines predicted that the “wave of the future” would be nuclear powered vacuum cleaners, flying cars, shopping malls, and ad-free television. Fascism was called the “wave of the future” by some 1930s academics. My favorite is a scholarly study that calls city-states – the staple of the ancient world – the “wave of the future.” 1940s Interior Secretary Harold Ickes famously said, “The so-called wave of the future is but the slimy backwash of the past.”

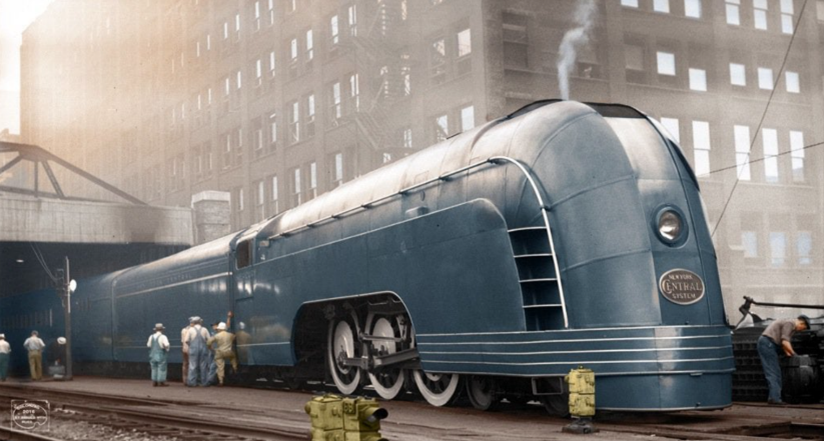

City planners and politicians continue to call mass transit the wave of the future, despite Americans’ continually declining use of ever more subsidized transit systems. Most of our lives, planners have been in love with light rail, high speed trains, and intercity buses – all century-old technologies. The first “bullet train” was not built by Japan in the 1960s, but by the New York Central Railroad in the 1930s. It was discarded by the 1950s as modern Americans abandoned trains in favor of cars and planes.

They still prefer their cars, and governments cannot change that, though they spend over $80 billion annually trying. The Biden Administration just allocated another $3 billion to California’s high speed rail fiasco, known by critics as the “train to nowhere.” That’s a sad comment considering the exciting initial promise. It started as a 2008 ballot initiative asking voters to approve $10 billion in bonds for a Los Angeles to San Francisco bullet train, to be completed by 2020. It sounded like a good idea to many, though it barely passed amid concerns that the price tag might grow. Ya think?

Before the end of the first year the cost had tripled. Then the route was changed to utilize existing tracks for large portions, so it is no longer considered “high-speed,” and it doesn’t go to either Los Angeles or San Francisco. If you want a slow train from Merced to Bakersfield you might be in luck, though the projected cost is now well over $100 billion, not primarily financed by voter-approved bonds but by the rest of the nation’s taxpayers.

Some advocates might still think that’s a reasonable price to get so many cars off the highways. But exactly how many cars would that be? If one looks objectively at the ridership of transit and rail systems across America, the sad answer is, hardly any.

The number of Americans who commute via public transit has been shrinking for decades, from about 7.8 million in 1960 to barely 5 million today, while the number driving to work has risen from 41 million to 124 million in the same period. The transit number further plummeted during the pandemic and has never recovered. Instead, the number of Americans working from home climbed from 9 million pre-pandemic to over 24 million since. American workers are not going back to riding trains. Transit use now comprises only 3.1 percent of American commuters despite the billions in subsidies. The federal government now pays either Metro or commuter rail expenses for its employees, yet the vast majority decline to use them.

A recent study by economists Yadi Wang and David Levinson compared costs and ridership on major mass transit projects from 1991 to 2018. They found in nearly every case the ridership was overestimated and construction and operating costs underestimated. What a shock.

Ridership is so poor that the Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility says the “passenger load factor of [large] intercity buses… should normally be about 30 to 40 percent.” In other words, buses running up and down the roads only a third full is considered normal, so that is now the industry standard goal.

How do Colorado leaders respond to this clear long-term national trend? By proposing to spend over $14 billion on a Front Range rail project, of course. They claim it would carry over 2 million passengers annually, between Pueblo and Ft. Collins, primarily on existing tracks. They point to the 160,000 cars a day counted on I-25 at Castle Pines, but those cars are not all going to the same place. So where would you put the station so those people would not still need their cars? In fact, as history shows, such a train would not carry 2 million passengers a year, no matter how much is spent on it. People may tell pollsters they would love to ride it, but when all is said and done, they won’t.

Colorado leaders seem to want their State to be more like California. But is this really the example Coloradans want to copy? Or is it the wave of the past?

Comments on this entry are closed.