A landmark era of American politics passes into the history books, with Jimmy Carter under end-of-life hospice care, and with the May 27 death of James Watt. Theirs was a moment in time that deserves remembering.

Most of America’s essential environmental laws passed in the 1970s with relatively bipartisan support. Yet today, no environmental issue achieves such consensus. What changed that spirit of cooperation in common causes like clean air and water, energy independence, or endangered species recovery? When did the environment become so divisive? The answer can only fully be understood in the context of two pivotal historic events: the Carter water project “hit list,” and James Watt’s appointment as Secretary of the Interior.

Just weeks after his 1977 inauguration, President Carter stunned the West by announcing what became known as his “hit list” of 32 water projects authorized by Congress that he wanted cancelled, causing a political firestorm that divided East and West like never before.

The “hit list” included projects westerners had sought for decades, including the Central Arizona Project and several others already under construction, negotiated for 20 years, with compromises forged through long and bitter struggles. Congress rebelled, though Carter eventually prevailed on many projects (he wasn’t completely wrong about all of them). But the political divide it caused has never really healed.

Carter misread public sentiment, alienating much of the West and helping elect Ronald Reagan in 1980 (Carter lost every southern and western state, except Hawaii, and the entire Mississippi River Valley). Many rural Americans had come to believe that he just didn’t understand or care about them. The fact that environmental issues were at the center of the divide was incidental at first. But he had set the stage for the most divisive era in conservation history.

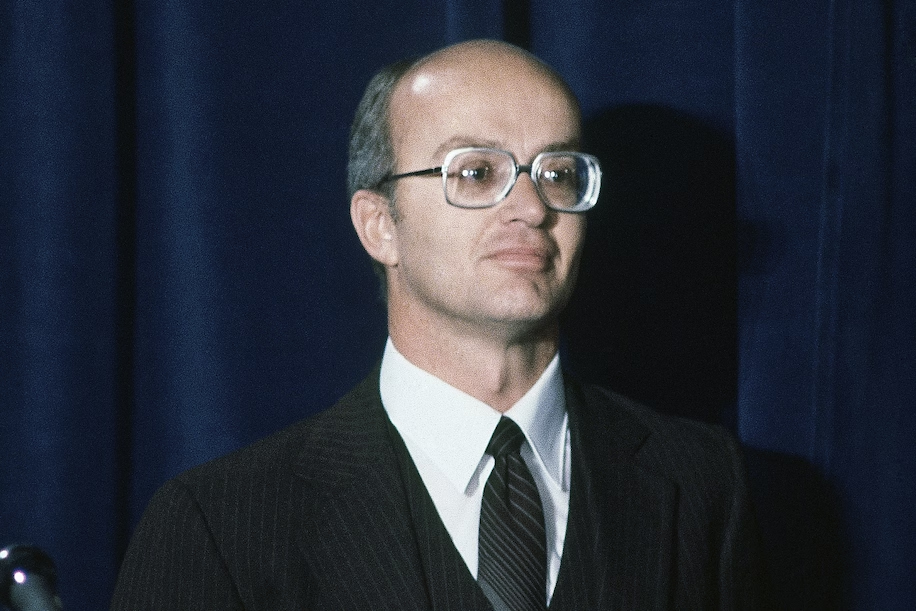

Shortly after his landslide victory, Reagan announced the appointment of James Watt as Interior Secretary. Virtually nothing about the environment has achieved a bipartisan consensus since.

Watt was more than just a westerner with a different perspective; he was a character, whom the media turned into a caricature. Before Reagan was even inaugurated, a now-famous cartoon lampooned Watt, shown yelling “When I’m Secretary of the Interior you environmental extremists are gonna tow the line!” The extremists he was yelling at were Johnny Appleseed, Smokey Bear, Woodsy Owl and Bambi.

Watt not only knew he would be controversial; he intended to be. He even warned the new President that he planned to make significant changes and “push the envelope,” predicting that if successful he wouldn’t last 18 months (he lasted 30).

Watt laid out an ambitious agenda, cutting funding for endangered species programs, and replacing some regulatory mandates with economic incentives. He proposed delegating some land management decisions to state and local governments, stopped further wilderness study areas in Alaska, and slowed federal land acquisition in the West, all of which led to feverish criticism from environmental groups and the media. One of the biggest firestorms came when he proposed to sell small tracts of federal lands no longer needed by BLM nor connected to national parks.

Watt’s policies may have been contentious, but he really became a lightning rod because of his reaction to the controversies. Far from backing down, he went on offense, challenging critics’ credibility, labeling some as “extremists,” “radicals,” or worse. The battle became personal for many, though Watt enjoyed the give-and-take. He told Newsweek, about the press, “They kill good trees to put out bad newspapers.” The media and the environmental industry had a two-and-a-half-year “field day.”

One environmental industry leader remembered Watt as the “worst thing that ever happened to America,” yet many activists consider him the best thing that ever happened to their movement. They turned him into something they had never had – an enemy with a public face, a world-class fund-raising tool. Membership in the Sierra Club had risen from 114,000 in 1970 to 200,000 by the end of that decade. But it increased to 325,000 after just 2 years of Watt’s tenure, and more than doubled before Reagan left office.

The ability to demonize an enemy is a Godsend to non-profits. Their success hinges on the ability to generate awareness, membership, and money. During Watt’s tenure, Americans joined environmental organizations in unprecedented numbers, and fund raising skyrocketed. That growth has not significantly slowed since, nor has the us-against-them view on both sides of environmental issues.

James Watt helped pave the way for today’s environmental divisiveness, after Jimmy Carter mapped the route. It was Carter who made Watt possible.

Comments on this entry are closed.