A New York Times “climate desk” reporter named David Gelles recently wrote a fascinating account of the internal battle plaguing the Sierra Club for three years. His lead explained that “Like many other American institutions, the Sierra Club was convulsed by the 2020 murder of George Floyd…” Some of his readers must have thought, “Wait, the Sierra Club? I thought that was an environmental group.”

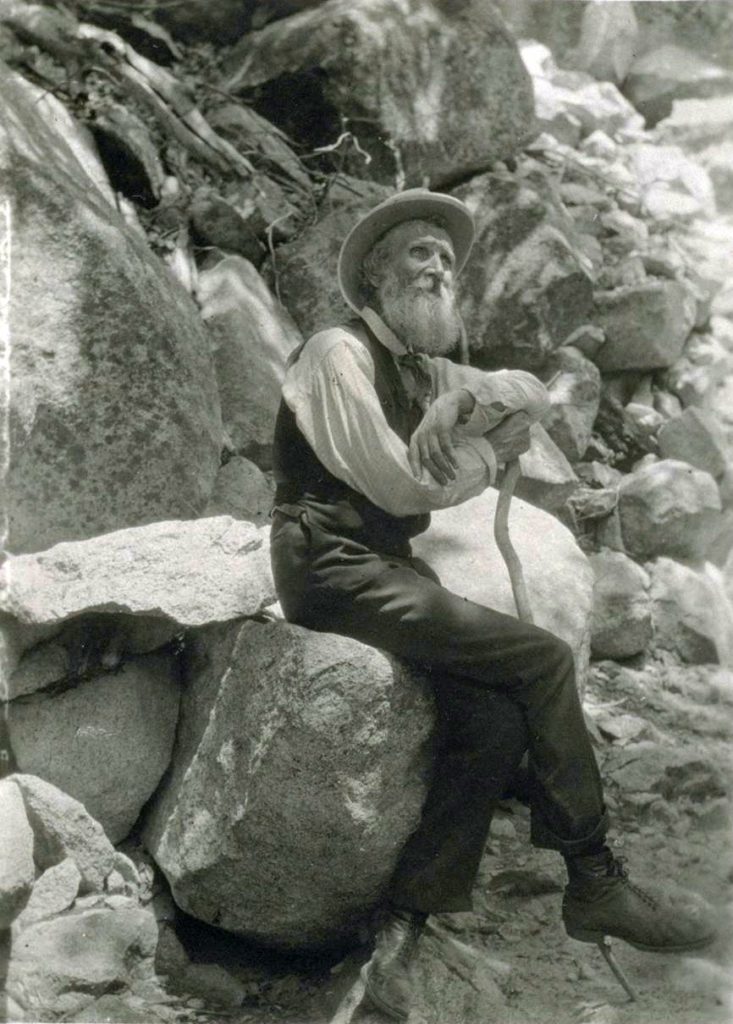

Indeed, it is the world’s best known environmental organization, whose founder, John Muir, is considered one of the founders of the modern conservation movement. Yet the group has been embroiled in a bitter and seismic internal war, not about any environmental issue, but about race. When the brutal murder of George Floyd touched off national protests, and gave rise to the “black lives matter” movement, some Sierra Club leaders decided the group should get involved in that.

The group’s executive director, Michael Brune, wrote a blog post, reprinted across the country, called “Pulling Down Our Monuments.” He claimed the Sierra Club had played a “substantial role in perpetuating white supremacy.” It was a bizarre claim, motivated purely by political opportunism and based on the obscure fact that a young Muir had written some unflattering views after his travels among native American tribes. To be clear, Muir was a product of the 19th Century, who thought like most Americans of the 19th Century. He said some things modern leaders would not say. But he played no role whatsoever in perpetuating any notion of white supremacy, much less a “substantial role.” He was not a KKK member, was never governor of Arkansas, managed no bus system in Montgomery, nor sanitation department in Memphis. He was a Wisconsin-bred northern Republican, an advocate of voting rights, an early progressive, a friend and ally of Theodore Roosevelt.

Michael Brune’s decision to demonize and attempt to “cancel” Joh Muir from Sierra Club history, stirred up a hornet’s nest that cost Brune his job, and led to two years of wrangling among board members trying to decide how to handle the history of John Muir. Most were afraid to defend Muir, scared of their own future in this new “woke” world, and the controversy has swirled unabated since. The Club has now hired a new executive director, a man whose actual name is Jealous – Ben Jealous, once head of the NAACP and more recently president of People for the American Way, the extreme liberal group founded by Norman Lear. The Times article says hiring Jealous was a decision intended to help the Sierra Club “emerge from the other side of that appraisal,” but in reality, it was a decision to put political correctness above its historic mission.

The Sierra Club has a century-and-a-quarter history of founding, nurturing, promoting, and furthering the American environmental movement. It is a proud history of protecting national parks, preserving wilderness areas, defending wildlife, and fighting for clean air and water. The worst strategy for the organization’s future is to dilute the passionate support of its million-plus members by getting involved in issues unrelated to the environment. It is a genuine concern about the environment that unites those members, and their donors, not all of whom necessarily agree on other issues – any other issues.

The organization found the same thing 20 years ago when it became embroiled in the immigration issue, partly because former Colorado Governor Richard Lamm was running for a seat on the Sierra Club Board and seeking to get the group involved in his anti-immigration battles. The divisiveness was bitter and although Lamm was not elected, some of those wounds remain to this day.

This is a discussion that was routine at Club 20 during the years I was president of the Western Slope advocacy group. The region’s communities are very diverse and divided on some issues, so the group should always try to stick to issues that unite the Western Slope – protecting its water, fighting for its fair share of highway funds, equal access to modern technology. Whenever the organization veers off into issues that are not unique to that region, such as taxes or foreign affairs, or when it presumes to represent the entire region on controversies like oil shale development, it runs the risk of dividing, not uniting, its members. In the long run, that weakens organizations, not strengthens them.

So the best advice for the Sierra Club’s leaders is simple – stay in your lane. Stick to what you are known for, and good at, and you will remain effective and relevant.

The problem with this argument is that no “lane” is distinct from other lanes: We can’t speak about the “environment” without also speaking to power, equity, and, yes, race. Most National Parks and protected areas, the world over, were created in the shadow of an untenable refugee crisis. Millions of Indigenous people were displaced as a result, leading to worse conservation outcomes to boot—particularly in dry ecosystems where fire suppression ensued. In this way (and in many others; see “environmental justice”), racism and colonialism are indeed baked into modern environmentalism, hardly “unrelated to the environment” if one understands history and how landscapes have been shaped over time. John Muir’s very conception of “wilderness” was, as you write, a product of colonial 19th century viewpoints. But that doesn’t make it excusable or undeserving of critique and reflection in the 21st century—especially from the perspective of an organization whose founder spoke of Native people as having “no right place in the landscape.” Muir didn’t think “like most Americans of the 19th century;” he thought like most *white* Americans of the 19th century, a distinction this write-up would benefit from including. One doesn’t need to be a KKK member to uphold white supremacy; one only needs to be explicitly or implicitly upholding colonial structures and ideologies through not actively contributing to their dismantling. White folks have a hard time understanding this, but it doesn’t make us inherently evil people. It just means we have work to do in undoing systems that were put in place by us, for us, and at the exclusion of other people.

It is the same silly argument used to tear down statues of Abraham Lincoln, based on the fact that he didn’t see everything the way people do in the 21st century. That doesn’t mean he shouldn’t be credited with saving the union and ending slavery. It just means he wasn’t perfect, as none of us are. John Muir apparently shared a common (almost universal) view among American settlers that was unflattering to Native Americans – that is undoubtedly true, and it is unfortunate. But it does not detract from his importance as a primary founder of the modern conservation movement. Indeed, he is indispensable to American history and no modern “woke” agenda can change that. Saying that “we can’t speak about the ‘environment’ without also speaking to power, equity, and, yes, race” is equally silly. We not only can, we should. Muir played no role in the horrors of slavery and white supremacy; it is not what he is known for; it is not what he should be remembered for. It bears no more importance to history than if he had also disliked Democrats (which he did) or loved foul language (which he did not).

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }