The recent news that scientists have finally produced a controlled nuclear fusion reaction that generates a net energy gain was greeted with substantial skepticism, but also a great deal of excitement. Some of the hype was a bit over the top, heralding the achievement at Lawrence Livermore Labs as a sign that a fossil-fuel free world is just around the corner.

For much of our lives, nuclear fusion has been considered the holy grail of clean energy, because it would create virtually unlimited energy supplies, with no carbon emissions and no long-term radioactive waste. I am not a scientist, so most of the technical explanation is a foreign language to me. In general terms, nuclear power plants are reactors that use energy from uranium to split atoms, which releases massive amounts of energy that is used to heat steam and generate electricity. That atom-splitting is nuclear “fission.” Such plants do not burn fossil fuels so they do not emit carbon into the air. But they do leave behind radioactive waste that can last thousands of years, is difficult to store safely, and has long been a political stumbling block to expansion of nuclear power.

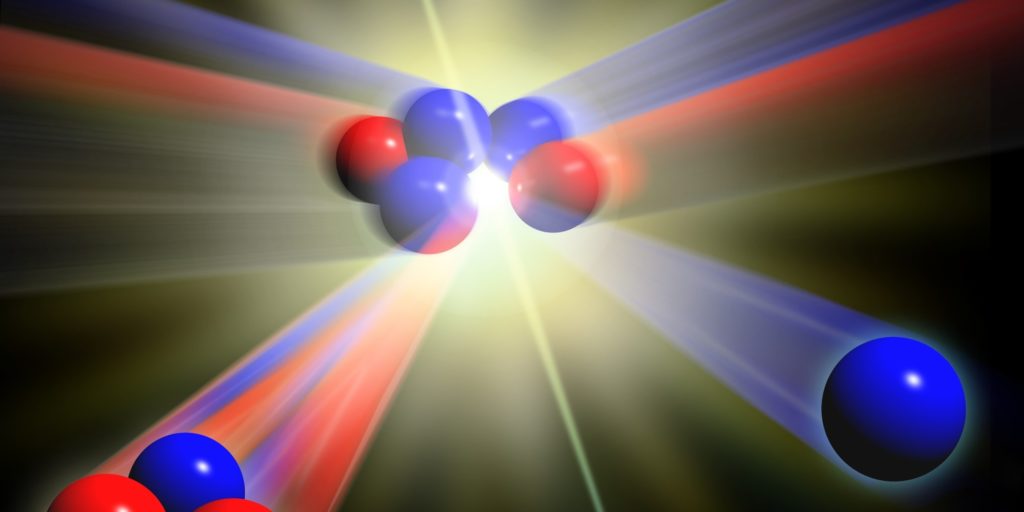

Nuclear “fusion,” rather than splitting atoms, combines them, literally fuses them together, and it releases many times more energy than fission. Fusion is the energy which powers the sun and the stars, and it requires heat that intense to fuse the nuclei together.

Fusion has been artificially achieved in laboratories before, but creating that kind of heat uses much more energy than it generates, so it has always been more of a dream than a realistic option. Still, governments and foundations have spent hundreds of millions on research and the equation may be changing. The Lawrence Livermore team has apparently achieved a technological breakthrough that resulted in a net gain of energy for the first time from fusion.

Predictably, since the government owns the lab in question, officials were quick to suggest that this will require massive funding increases to figure out how to scale the technology to today’s consumer needs. And skeptics like the Wall Street Journal editors were equally quick to warn that any commercial use of fusion technology is still decades away.

I always think the prospects for new energy sources are exciting, but the reality is that however promising they may be, every new alternative invariably encounters resistance and opposition. There will always be a corps of activists who flatly oppose all forms of energy, and this will probably be no exception. As soon as they essentially killed the coal industry and forced utilities to switch to natural gas, the attack on fracking and other means of producing natural gas began, including opposition to exporting liquid natural gas (which could wean Europe from dependance on Russia). No sooner had a massive wind energy industry peppered the country with giant wind farms than opponents began trashing that technology, which kills birds, consumes lots of minerals, and creates noise issues. Solar panels now attract opposition, from neighbors who find them unsightly to activists against mining the minerals from which they are made.

There are naysayers everywhere, and probably always will be. I was excited when a company called WaveGen built a 300 kilowatt plant on the west coast of Scotland in 2000, the world’s first grid connected commercial scale facility to generate electricity from shoreline waves. With a remarkably small footprint, it used a water column with turbines that generated power when waves raised and lowered the column thousands of times every day. It proved profitable on a commercial level, but local opposition prompted the owners to shut it down by 2013 and the technology has been all but abandoned. I have also thought the potential is huge for tidal power, the efficiency of which France has demonstrated at the Rance Estuary station for over 50 years. Yet any use of the power of oceans also faces stiff opposition from people concerned about wildlife and other side effects. There is similar opposition to biomass, geothermal, and virtually every other source of energy.

Do not be deluded, though, into thinking all this opposition stems from genuine concern about the environment. Some of it does, of course. But we should be honest enough to admit that there are also people opposed to any growth in energy because it might lead to the growth of population, a higher standard of living, more manufacturing, production, and especially consumption.

For generations, Americans have been told that they are running out of oil and gas and a crisis is coming. In 1920 the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that America had only 12 years of reserves, and new discoveries were diminishing. By the end of the 1920’s the Federal Oil Conservation Board, concerned about the largest year of auto sales yet, announced the impending danger that the country would run out of oil in the near future because of the new mania for cars. American oil production is roughly 20 times higher today than in 1920 and the reserves are hundreds of times greater.

We now know there is more natural gas in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus shale than the government once thought existed in the whole country. We’re not running out of energy and we never will. That’s because Americans continuously find more, develop new ways to get to existing sources, and discover new ones. That is the result of a different kind of fusion – one that combines the power of free people to think and create, and to reap the rewards of their labors.

My friend Craig Rucker, president of the Committee for a Constructive Tomorrow, writes that it’s OK to be sober about the scientific and engineering challenges facing the development of nuclear fusion technology, though we can guardedly say it has the potential to change everything. So rather than over-hyping the achievement, or being overly pessimistic, as Craig says simply and rightly, “Let’s do the science and find out.”

Comments on this entry are closed.