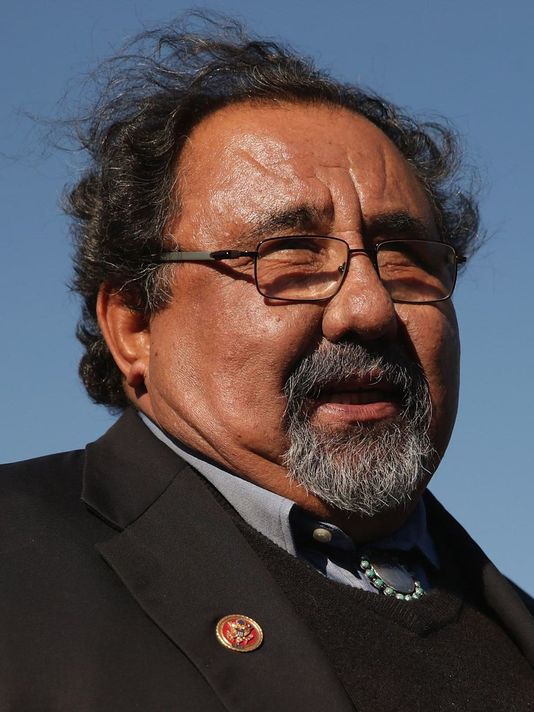

There is much ado about congressional leaders double crossing Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV), promising a vote on his environmental permitting reform bill in exchange for his vote for the massive climate bill. No sooner was that bill passed than Democrats on the House side announced their refusal to schedule a vote on Manchin’s. In many reports, including my own, it appeared that House leaders, especially Natural Resources Committee chairman Raul Grijalva (D-AZ), were miffed that they were not consulted when Senate leaders made the promise. They certainly had no intention of keeping it.

It turns out there is more at stake than bruised Capitol Hill egos, legendary though they are. Obviously, Grijalva and his environmental allies do not support Manchin’s attempt to shorten the often-daunting federal permitting process for infrastructure projects. But it’s more than that. Manchin’s approach is 180 degrees opposite the one they have worked on for years, which they call the “Environmental Justice for All Act.” In fact, Grijalva would lengthen the permitting process, enable more lawsuits and delays, making permitting more difficult, time-consuming, and expensive.

In this Congress, there is no chance Grijalva’s bill will pass either House, but not because of a process dispute concerning how permitting should work. There is a much more fundamental issue that divides the two sides. Supporters call it “environmental justice” because nobody is really opposed to either the environment or justice. In this context, it is a buzz word for the perennial issue of “cumulative impacts.”

In truth, much of the Grijalva legislation was already adopted as part of an emergency wildfire bill this summer. Among other provisions, that made it easier for opponents not only to sue agencies for issuing permits, but also to claim discrimination under the Civil Rights Act if the plaintiffs are part of an “underserved community.” However, supporters were not satisfied because it did not include their most-wanted provision, language on “cumulative impacts.” That would require permitting decisions under both the Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act to consider the “cumulative effects” of emissions.

Thus, no new permit could be issued for a power plant, mine, road, bridge, wind farm, or other development without adding its projected emissions to all those already existing. Even a small project might be stalled because it would add just a bit more of some pollutant in a metro area already struggling with high levels. It might add just a tad more salinity to a river already considered too saline.

That seems logical and reasonable to most, at first glance. In Colorado, for example, we worked for years to address cumulative impacts of water diversions. No single diversion is so large that it deteriorates water quality to the degree that it is no longer usable downstream. But over a period of decades, hundreds of small diversions certainly can do so, and the Colorado legislature has addressed it several times. Similarly, no single source of air pollution is so bad that it destroys air quality for an entire city, yet thousands of small sources can add up to hazardous levels in some areas. So, it sounds reasonable that government ought to say at some point, enough is enough.

The problem is that drawing the line runs headlong into an enormously important founding constitutional principle about the proper role of government. That is, who gets to decide which businesses can exist and which cannot?

In some ways, this horse already left the barn, especially with respect to water rights, where we clearly make a legal distinction between users who were there first and those who apply later. But that is about using a limited commodity, not creating something new. It is more difficult to tell a local electric utility it cannot build a badly needed power plant because the “cumulative” emissions for the valley, county, or state are already too high. That would drive up the cost of existing power generation, just as limiting the construction of new homes in Aspen drives up the price of already-existing homes.

Taken to its logical extreme, how different is that than a local government deciding it will only allow four restaurants, denying permits for any fifth applicant? The free market can determine how many restaurants a town will support, so such a rule would amount to nothing more than protection for existing businesses.

The reason Grijalva’s bill cannot pass is that many leaders recognize there is a fine line between regulating “cumulative impacts” and using the power of government to protect businesses from competition.

Comments on this entry are closed.