President Jimmy Carter’s Office of Management and Budget Director, Bert Lance, is best remembered for a corruption scandal involving Calhoun National Bank. But he is also the one who popularized the corny phrase, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” “That’s the trouble with government,” he wrote, “Fixing things that aren’t broken, and not fixing things that are.”

Another name from the past, former Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt, is still trying to tinker with the Colorado River system, which “ain’t broke.” Some people are confused about that, because of the growing alarm about historically low water levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

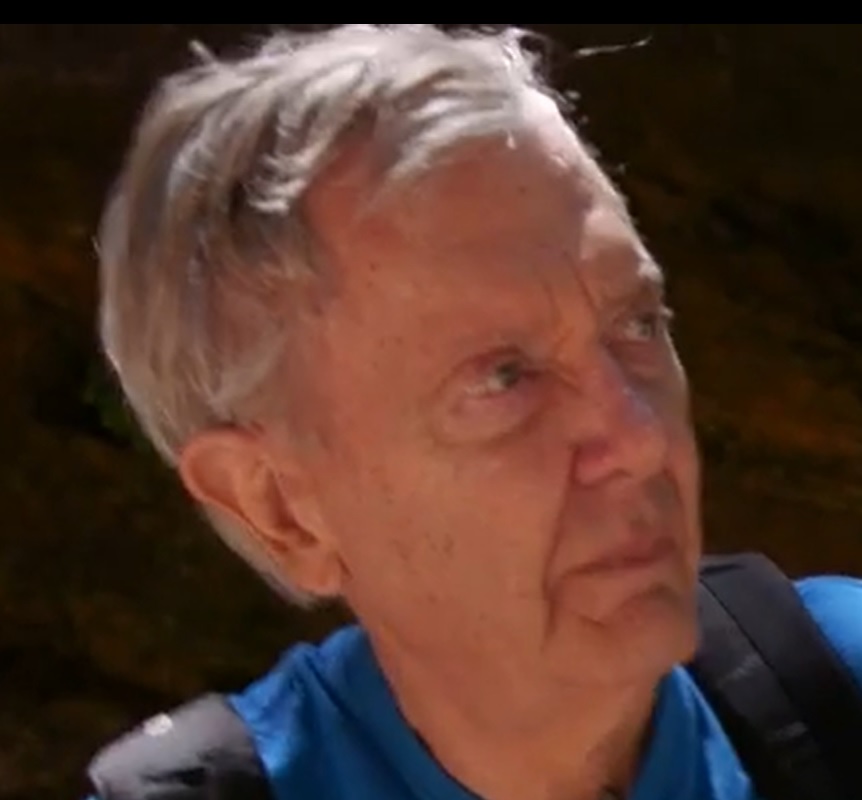

In the midst of another historic debate about the Southwest’s two main reservoirs, Babbitt has decided to weigh in, two decades after leaving office, opining that we must renegotiate the Interstate Compact. The ex-Interior chief, now 84 and mostly retired, apparently thinks Colorado River issues are so complex that we are desperate for his sage advice. His legendary ego notwithstanding, western water leaders are not anxiously awaiting Babbitt’s wisdom about Lake Powell or Lake Mead.

Those lakes represent more than water storage for both the Upper and Lower Basins, habitat for hundreds of species, and popular outdoor recreation. They are also crucial to the western power grid. Lake Powell’s 1,320 megawatt power plant, and Lake Mead’s 2,100 megawatt plant, provide nine billion kilowatt hours annually to utility companies from Nebraska to California. But even electricity is not the most important purpose of those dams.

The vital function of Glen Canyon Dam is to provide the mechanism to administer the Interstate Compact, which allocates the river’s water among 40 million people in seven states.

The 1922 Compact divided the water equally between the Upper Basin (Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico) and Lower Basin (Arizona, Nevada and California), divided just below Lake Powell. The annual average of 15 million acre feet (MAF) was split, 7.5 MAF for each basin. Nowadays, the actual flow is around 11-12 MAF, not 15. But as the Compact is interpreted, the Upper Basin must deliver to the Lower Basin 7.5 MAF, not every year, but on a rolling ten-year average. Lake Powell is the spigot which makes that delivery possible and measurable. That makes Lake Powell absolutely essential to the Upper Basin.

Now, Babbitt wants what Lower Basin officials have always wanted – to change the Compact. Trouble is, Babbitt has no credibility in that conversation, for two reasons. First, his heart has always been with his native Arizona, where he was Attorney General and Governor, and argued for more Lower Basin water – he is neither dispassionate nor objective. Second, Babbitt is the one who pulled the plug, and now wonders why the tub is draining. He filmed himself opening the gates at Glen Canyon Dam to create a massive flood, 45,000 cubic feet per second exploding into the Grand Canyon for seven days, a raging deluge of water and sediment. One environmental writer gushed, “This action signifies that our society is beginning to understand that the release of energy to restore ecosystems is at least as important as the storage and release of the same energy to make electrical power.” Babbitt was gleeful as a child with a new toy, playing with control room gadgetry, with no thought whatsoever about how the Upper Basin would replace the lost water. He created the “Glen Canyon Adaptive Management Program” to increase fish flows at the expense of water storage.

Finally, Babbitt famously told a Trout Unlimited audience that he wanted to be the first Interior Secretary “to tear down a really large dam.” He was quickly reined in by congressional allies, and claimed he only meant a couple small dams in Washington. But within a year he advocated removing four Idaho dams, and personally took a sledgehammer to another in California. Most leaders in the Upper Basin knew precisely which large dam he really meant, coincidentally while the Sierra Club launched its campaign to “restore” Glen Canyon – by removing Lake Powell.

Babbitt simply has no credibility on managing the Colorado River.

Conversely, Brad Udall of CSU’s Colorado Water Institute, says the Compact must be reinterpreted, not renegotiated. He believes, as I do, that Upper Basin delegates in the 1922 Compact meetings would never have agreed to a fixed obligation irrespective of how the River’s average flow evolved. As Brad says, to assume that was their intention violates common sense.

The answer is not to alter the Compact as Babbitt wants, but to interpret its requirements according to actual flows, on a rolling ten-year average, maintaining every state’s relative share under current law. That’s fixing what is broken, and leaving alone what isn’t.

Comments on this entry are closed.