Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Touton recently told a Senate Committee the government must reassess its management of the Colorado River Basin, because of unprecedented drought. She cited the historically low levels of both Lake Powell and Lake Mead, though her testimony was long on drama and short on plans. In fact, she offered no indication that she understands the role her own agency has played in what she admits is a crisis.

She thinks the crisis is about drought, but it is more about management. That’s because the government can’t do much about snow volumes, but it has complete control over its management of reservoirs. The existing “drought contingency plan,” agreed upon by the seven states with legal rights to Colorado River water, expires in 2026. She urges changing the management plan sooner, but without explaining how.

The Colorado River Research Group, a team of scholars at Utah State University, studies this River system, from perspectives in social, physical, and biological sciences, along with water law and public policy. In 2018, they highlighted the role of policy decisions in draining Lake Powell, in a paper aptly titled, “It’s Hard to Fill a Bathtub When the Drain is Wide Open.” That is precisely what has happened at Lake Powell, yet the report has been largely ignored. It should be required reading for everyone concerned about the Colorado River.

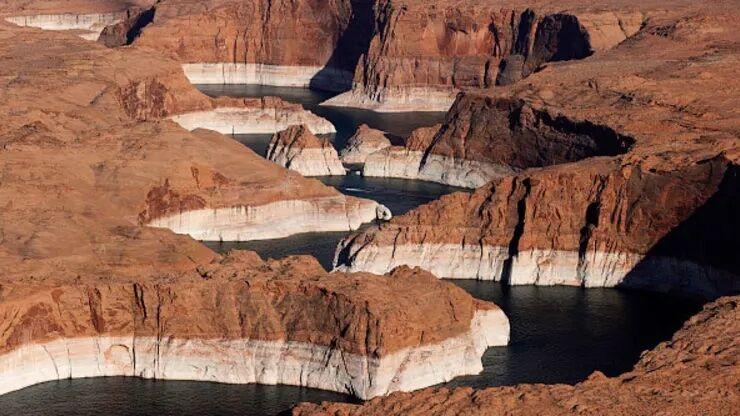

Lake Powell was created for the primary purpose of administering the Interstate Compact – ensuring the Upper Basin states can deliver the water they are required to send downstream, even in dry years. It was completed in 1966 and finally filled to its 27 million acre-foot capacity by 1980. But since 2000, the water level has dropped 94 feet, even though the Upper Basin states have consistently used only 60 percent of their entitlements. The lake holds barely 10 million acre-feet today.

In reservoirs designed for multi‐year carryover storage, “declines are expected in dry years, and recovery is expected in wet years.” But at Lake Powell, “When large inflows do occur, current operational rules immediately trigger large releases.” In the extremely wet year of 2011, for example, inflow at Lake Powell was five million acre-feet above average. But the Bureau immediately opened the gates and sent it all downstream to Lake Mead, benefitting California, Las Vegas, and fish. No wonder Lake Powell cannot recover during wet years.

The report acknowledges that several dry years contributed to the water level drop, “but ultimately it is the operational rules that are slowly but surely draining Lake Powell.” Under the Interstate Compact and in international treaty, the Bureau was supposed to release about 8.3 million acre feet per year for the Lower Basin and Mexico. But in all but four years between 2000 and 2018, the agency released more than that, a cumulative total of 11 million acre-feet beyond what is required. “Had those excess releases remained in Lake Powell, the lake level would not have declined,” as the report notes.

The Bureau’s main concern is “deploying emergency strategies” to ensure enough water for hydropower generation, at both Powell and Mead. To keep those revenues flowing, this year the Bureau sent another million acre-feet to Lake Powell by draining Blue Mesa and Flaming Gorge Reservoirs, to the point of ending seasonal boating operations, at tremendous cost to the Colorado and Wyoming economies.

That’s the priority, because hydropower revenues fund the government’s favorite regional projects: the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program, the Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Program, the San Juan Recovery Program, and the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program. That’s ironic, because those programs continually demand greater flows for fish recovery. That very strategy is now draining Lake Powell, not only their funding source, but also the only means for guaranteeing regular water flows of any amount.

To be clear, it was the Interior Department’s Bureau of Reclamation – not global warming – that changed the rules for managing river flows. The “Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program” was a Clinton-era initiative of then-Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt, in consultation with favored environmental groups, to increase fish flows – at the expense of water storage, compact compliance, and recreation, the purposes for which Lake Powell was built. Babbitt wanted a process for “cooperative integration” of dam operations and “downstream resource protection.” In other words, the purposes of the dam must be balanced against the needs of the fish, and environmental groups must be at the decision table with actual water managers and state officials. The Bureau defines “adaptive management” as “a dynamic process where people of many talents and disciplines come together to make the right decision in the best interests of the resources.” Not the best interests of the people for whom that reservoir was built.

Commissioner Touton thanked Congress for the $8.3 billion it gave the Bureau as part of the Biden infrastructure bill, including $300 million designated for “drought contingency planning.” That much money could restore healthy watersheds to millions of acres of public lands, and we know that thinning forests to their natural density would recover much of the missing water in the West, irrespective of climate change and drought. I doubt she will spend a nickel of the money on that. Rather, they’ll continue to drain the bathtub, while complaining that it isn’t filling fast enough.

Greg: Great article. I just posted on Facebook. Those are very scary pictures meant to stir up fear over Climate Change to help the climate warriors in government get their way! Its so important people know the truth and thanks for what you are doing! Rob

Comments on this entry are closed.