Steven Spielberg’s first block-buster hit as a director was 1975’s Jaws, and we all know sequels are rarely as good as the original. Yet it was 1978’s Jaws II, directed by someone far less famous, that film historians often credit with the movie industry’s best-ever tagline, “Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water.”

In the same way, a new study gives us pause about the decades of progress Americans have made in cleaning up air pollution. I know, there is a new study every other week, but this one has considerable credibility, being from the National Center for Atmospheric Research, written by Princeton researchers, funded by the National Academy of Sciences, and published in the journal Nature Communications. This research points to a dramatic increase in carbon monoxide levels during August, a month when carbon monoxide levels have historically remained low. And it predicts a tripling of western U.S. particulate pollution in the coming years, because of wildfires.

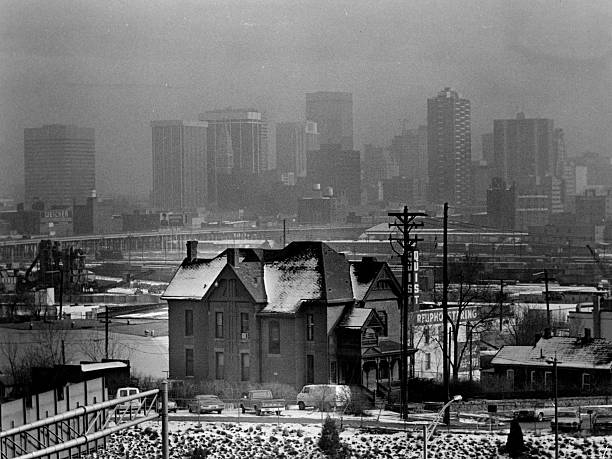

Just when Americans had every reason to be proud of astonishing achievements, especially the near disappearance of the thick brown clouds that hung over many cities in the early 1970s, when the Clean Air Act was adopted.

As EPA points out, “Great progress has been made in achieving national air quality standards, which EPA originally established in 1971 and updates periodically based on the latest science. One sign of this progress is that visible air pollution is less frequent and widespread than it was in the 1970s.” That progress is despite the fact that EPA has since tightened the standards for five of the six common pollutants subject to regulation. Today, particle pollution and ground-level ozone are substantially lower, and the entire nation now meets the strict carbon monoxide standards.

“For more than 40 years, the Clean Air Act has fostered steady progress in reducing air pollution, allowing Americans to breathe easier and live healthier,” the agency’s website boasts. Indeed, between 1970 and 2020, the combined emissions of the six common pollutants dropped by 78 percent. Improved technologies, such as smokestack scrubbers, vehicle emission improvements, low-VOC paints, and many others, helped reduce sulphur dioxide by 91 percent, and lead by 86 percent, since 1990. Particulate pollution has plummeted – until now. And the reason, according to this study, is the West’s massive catastrophic wildfires. In more than half of the western states, the largest wildfires in history were during the last two decades (including both Colorado and California). The wildfire season now averages 105 days longer than in the 1970s.

The report says these intense wildfires are altering the seasonal pattern of air pollution, causing a surge in unhealthy pollutants in August, undermining clean air improvements, and posing potential health risks to millions across the continent. Yet ironically, these researchers call for drastic mitigation measures – to mitigate climate change, not wildfires.

It is an ongoing failure of academics, and the government agencies that fund them, that they cannot find solutions to America’s forest health crisis. They instinctively default to the climate change narrative, because they assume nothing can be done about the condition of the forests themselves. After decades of sloganeering (“Save the old growth,” “Save the spotted owl,” Stop the clear-cutting”), the anti-forestry mentality is so thoroughly engrained in academia and government that they cannot even consider proper forest management as an alternative to wildfires.

This study’s abstract says, “Even with strong mitigation [for climate change, particulate pollution] in the western US would increase 50 percent by midcentury.” It adds pessimistically that “the consequential pollution events caused by large fires during 2017–2020 might become a new norm by the late 21st century.” That may be because there is little the U.S. government can do to mitigate climate change. But there is much it can do about the management of its own lands.

Coincidentally, California’s Marin Independent Journal simultaneously published a feature calling for landscape-scale vegetation management, including significant clearing, herbicides, and logging to reduce fuel loads, prevent forest fires, and reduce air pollution. The writer documents numerous management projects that have succeeded in restoring more natural, less overgrown, forests. The only failing is his assumption that “defensible space” is needed around homes, roadways, powerlines and other urban structures. That ignores the overgrowth problem throughout national forests in most of the West, where massive unnatural fires will continue their destruction without active management. The resulting air pollution will threaten lives and public health, just when we thought it was safe to go outside and breathe again.

Comments on this entry are closed.