For generations, playground bullies have repeated the rhyme, “finders keepers, losers weepers,” as justification for theft. It’s a catchy phrase but it does not vindicate stealing. Adults sometimes put it differently, citing an equally dubious phrase, “possession is nine-tenths of the law.” But it isn’t. The mere fact of possession does not equate to ownership. If it did, there would be no deterrent to common thievery.

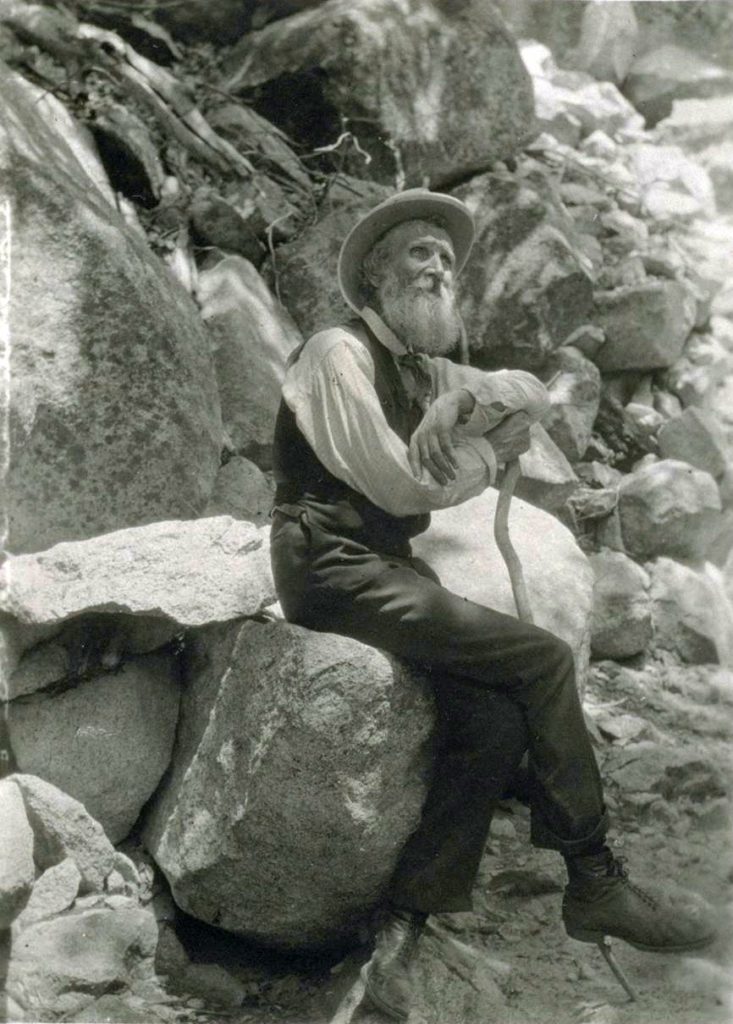

Thankfully, there is more to ownership than that, whether the property in question is a set of marbles on the playground, or a tract of land. There is a great new debate raging among historians about what constitutes land ownership, thanks to a series of blog posts from the President of the Sierra Club, Ramon Cruz, and the group’s former executive director, who lost his job over the dispute. They accuse the conservation movement’s greatest hero, and the Sierra Club’s own founder, John Muir (1838-1914), of racism, citing some of his early writings as evidence that he was not especially fond of the Native American tribes he encountered in his travels. Cruz wants the Sierra Club to work not only on conservation, but also on the “broader movement for social and environmental justice.” He wants Muir “cancelled.”

I’ve always thought accusing people from the past of racism is a slippery slope, as nearly everybody in the 19th Century shared that character flaw with Muir to some degree. By today’s standards, very few historical figures could pass the political correctness test. Cruz nevertheless wants to reassert tribal ownership of New York, not that any modern people would want to manage such a crime-infested, high-tax, low-growth metropolis, which its own citizens are abandoning in droves. No, these historical revisionists want the money, which would be due if everyone agreed that their ancestors once owned it. Did they?

Cruz admits that “We were not the original inhabitants of most of the places that we step in. There has been for millennia other groups and other nations that were there…” And therein lies the crux of the debate. Namely, who was there first, and does that mean the land belongs to their descendants?

New York was once occupied by the Lenape people, a very loose association of independent villages speaking similar Algonquin languages. But they were not the first, either. Did they take the land from their predecessors? Archeologists know there were people there 9,000 years earlier. The various Lenape bands were frequently at odds with Iroquois, Susquehannocks, and each other, sometimes going to war, so the territory changed hands numerous times.

Then came the European settlers, also claiming the land by occupying it. The Dutch supposedly bought it from the Indians in 1626, but Verrazzano had claimed it for France a century earlier. Portugal had already “discovered” and claimed the Hudson River, decades before Dutch governor Peter Minuit bought Manhattan. Historians think he bought it from Seyseys, Chief of the Canarsee Indians (a Lenape subgroup), though it was supposedly controlled by the Wappinger tribe. They weren’t there, but the Canarsee were, so they felt entitled to sell it. Thus, among the diverse tribes who occupied various parts of Manhattan at various times, who really owned it?

Cruz argues that it was Lenape territory because that’s who occupied it. But that begs the uncomfortable question, if mere occupation conveys ownership, isn’t it part of the United States today, since that’s who occupies it now? Or does it belong forever to people whose ancestors once did? He and others argue variously, that the Dutch bought Manhattan from people who had no right to sell it, or were tricked into making a bad deal, or might not even have known they were selling it. Why would that matter, if occupation alone defines ownership?

When the English settled Jamestown, Virginia in 1607, it was the land of Powhatan and his people, because he (and probably his father) had conquered and subdued six other tribes. He then occupied Virginia, though others were there long before. Similarly in Colorado, Utes once occupied the territory, though they were hardly the first. Others were there at least since the clovis culture and other hunter-gatherers during the Ice Age, at least 14,000 years ago. Basket makers were there as early as 1500 BC, Pueblo tribes by 500 BC, and the Anasazi from about 350 to 1300 AD. In 2000, evidence was discovered that a band of cannibalistic raiders had swept through the Anasazi villages, killed the inhabitants, and eaten some of them. About 1250, a major battle was fought between the Anasazi and unknown enemies. Did the Anasazi abandon the area because of drought, as has been supposed for generations, or because of pressure from other conquering tribes? A period of mound-builders followed, and by 1600 the Utes had moved in, displacing earlier inhabitants. Did it thereby become Ute land forever?

Property ownership is determined by laws of the state we now live in. Our forebears may not have come into possession in ways we’re proud of, but neither did their predecessors. Values, principles, and customs evolve with the times, which is why judging people of the past by standards of today is as foolish as conceding that playground bullies own all the marbles.

Comments on this entry are closed.