This month, voters in five counties of eastern Oregon voted to instruct local officials to take action to secede from Oregon, and join Idaho instead. Separatist movements are not especially uncommon in the West – several have sprouted in Colorado over the years – but it is rare that voters actually have a chance to weigh in officially.

Rural activists say they are tired of being ignored, and outvoted, by people in the large cities who are isolated from the interests of rural communities, both geographically and culturally. That’s why activists in Northern Colorado recently proposed creating their own state, free from political domination of Front Range cities. I remember in the 1990s when some Western Slope activists proposed creating their own state, for the same reason. In one recent example, voters in Boulder and Denver voted overwhelmingly to introduce wolves, not in their own counties, but West of the Continental Divide, where the ballot measure was strongly opposed by the voters who must now live with the results. That is but one of many divisive issues that separate rural and urban interests. Think especially about water, or highway funding.

Commentators watching the Oregon vote say the explanation is much simpler and more partisan than any ballot initiative. In short, Oregon voted 56 percent for Joe Biden, with most votes cast in Portland and Eugene, whereas the five counties moving towards secession all voted for Donald Trump by at least 69 percent. They are counties with economies historically dependent on agriculture, mining, and forest products – industries unpopular with urban voters – but most media reports say the move toward separation is purely partisan. In truth, it is that, too. But whether those rural Oregon voters were motivated by bitterness over the 2020 election, or by concern about the future of natural resources industries, the solution may be the same.

It is difficult not to compare the similar movement by activists on the other side, to grant statehood to Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico. Their motivation is largely the same, and in either case, creating new states could alter the balance of power in the U.S. Senate. It is precisely reminiscent of the divide leading to the compromise of 1820, known to history as the “Missouri Compromise.” I don’t know if anyone studies such history anymore, but that era offers a surprisingly simple solution for this one.

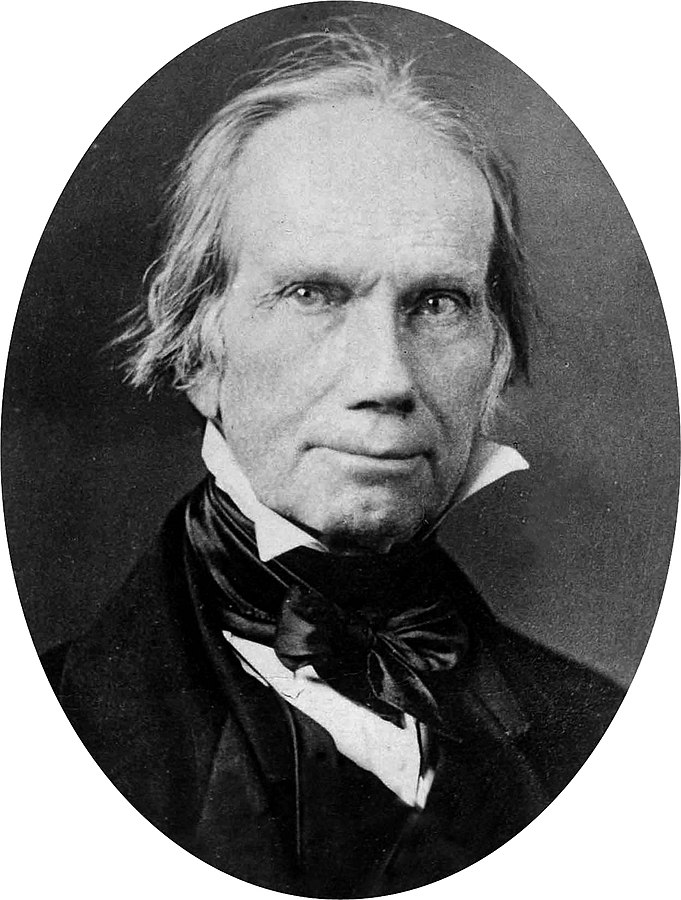

Obviously the issues dividing America today differ from those of the 19th Century, but the partisan situation is eerily similar. The senate was divided exactly in half (sound familiar?) between north and south, so no agreement could be reached on admitting Missouri, which would be another southern slave state. After several unsuccessful legislative battles, House Speaker Henry Clay finally offered the deal – to admit Missouri as a new southern state, and Maine as a new northern one (nine counties separated from Massachusetts). Henceforth, new states would have to be admitted in pairs, so as not to upset the delicate balance. California was admitted in 1850, but with the requirement that it send two senators divided on the slavery issue. The Missouri deal essentially held for over 30 years, and its repeal hastened the onset of the Civil War.

Oregon pundits are speculating about the likelihood of the Democrat-controlled legislature agreeing to let those five counties go. That seems unlikely, but the discussion might be missing a larger picture. An 1820-style compromise might provide the answer for maintaining today’s balance of power in the Senate, even while addressing voters’ concerns in rural western counties, and in D.C.

Under this new “Oregon Compromise of 2021,” new states could be admitted to the union in pairs. If one side got to admit D.C. or Puerto Rico, the other side would get a new rural state, say Western Colorado, Eastern Oregon, or South Georgia.

From a historical perspective, America’s current situation is more like that of 1820 than you might suspect. Today’s political divide is not about slavery, though there is clearly a racial component to it. The divide is not north-south, but it is just as geographically distinct, now urban-rural. Vast numbers of people on both sides think those on the other side no longer care about them, devolving us almost into two separate countries, culturally.

This is no time to widen the gulf. It is a time for a lasting compromise, one that might preserve the balance that is crucial to a republic’s function. The Oregon Compromise. I wonder if there are any statesman like Henry Clay to negotiate it.

I like this one alot. Thanks for the history lesson as well. Unfortunately, some of the divide today is intentional and personal with a dose of NIMBY – not in my back yard. The sad note is that many don’t understand the unique thought that went into the building of our country and our form of government, and therefore, are low on the learning curve of identifying and crafting strong solutions.

The conversation around statehood of D.C. and Puerto Rico is not equivalent to any secessionist movements. One means recognizing those already governed by US federal policy who have no representation, while the other involves those dissatisfied with their representation. This is an important distinction. Those is Oregon, or Colorado, who are currently spinning up the secession machine again might benefit from a reminder that a sizeable portion of the land they wish the secede with is federally owned and managed. All too often we heard stories of the supposed urban vs rural divide, all the while ignoring the fact that much of the land surrounding rural communities is in the public trust. While it may be geographically adjacent to rural communities, and while it may be leased and worked by those same communities, that land does not belong to those communities. These secessionist movements seem to spin back up every time we have a Democrat in the white house. It seems to be the GOP equivalent of the so-called ‘cancel culture.’

Ultimately, it’s nothing more than political theatre. I suspect most know that, but just in case, readers should familiarize themselves with the Constitutional provisions surrounding statehood. In short, Congress would need to approve any secession movement. Any of these movements would have a snowball’s chance in hell of leaving the U.S., though I’ll recognize that remaining in the US as a new state has a slim chance.

“New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new States shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of ay other State; nor ay State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.”

In the case of Oregon, the state legislature would need to consent. Given that the folks wanting to secede from that state are doing so for political reasons- specifically, feeling that they aren’t being fairly represented in the legislature, I don’t see this panning out.

Statehood for D.C. would need to follow a similar path. Difficult, but the political will may be there. Puerto Rico, however, is already a US territory and would not “take” land from an existing state. That path is considerably easier, in my opinion.

It seems to me, Mr. Walcher, your primary interest is not disrupting the political balance in our current Congress. I do not believe that is an admirable goal. We should seek fair representation, not political balance. Minority protections are important, but this calculus to ensure Congress remains divided seems politically motivated to ensure the minority powers can continue to stall the objectives of the majority. For a Republican voter, that may be appealing today, but we know how the political powers shift. Today, it’s a Democrat in the White House, but tomorrow? Would you want to see your political agenda, presumably supported by a majority of Americans, derailed by minority powers just to achieve balance?

Balance is no goal to set for politics. Fair representation is.

Gee, thanks for “reminding” us that so much of the West is federally owned, as if we need reminded. Such condescension is a classic example of why so many rural people feel unrepresented and un-cared-for in the current political climate. The movements in places like rural Oregon or Colorado have nothing to do with Washington, D.C. They are about the domination of voters in urban centers who ignore the interests of their own rural neighbors, treating them not only with ambivalence, but often with contempt. Nor are these rural folks interested in leaving the U.S.A. The fact that anyone thinks that’s what these movements are about underscores how little they understand the nature of this frustration. Rural people are well aware of the need for approval of new states, both by the existing legislature and by Congress. They were not born yesterday. And above all else, they are weary of being told about “fair representation” when they see none of it. D.C. activists who rail about “taxation without representation” ought to understand the feeling, but clearly do not. Their problem deserves a solution (which I have offered), and so do the problems of other underrepresented populations.

Excellent. You may be spot on… there are no more statesman like Bill Armstrong around. I wonder if we could get John Andrews to throw his hat in the ring…?

K

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }