I’m often amazed how we get wrapped up in the mind-numbing details of government processes, while completely missing the “big picture.” We can’t see the forest for the trees, as they say, because we’re so caught up in arguing the nuances of legal language that we forget to ask, “Why are we doing this?” What is the important goal, and how does this detail advance it?

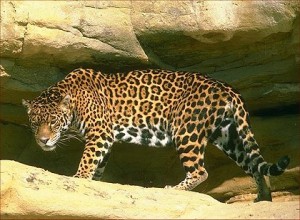

We have discussed many examples in the enforcement of endangered species laws. But I couldn’t help shaking my head at this one. A small article appeared in a couple insider newsletters, but otherwise completely escaped most public notice. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), the primary enforcement agency for the Endangered Species Act, issued a revised ruling and “Incidental Take Permit” to a proposed mining operation south of Tucson, related to its impact on the habitat for the jaguar. “Incidental take” means, simply put, that it’s acceptable if normal operations result in the death of the jaguar.

What’s so unusual about this new rule is that it is considered by its own government authors as likely to result in the demise of the jaguar. I say “the” jaguar – singular – because the government believes there is only one left in the entire United States. And it is now perfectly OK to kill it (as long as it’s not on purpose).

The irony of selective enforcement defies logic. Elsewhere (i.e. in Colorado), listed species like the lynx are used as a tool to regulate land uses including skiing, timber harvesting, grazing, drilling, and yes, mining. If the designated “critical habitat” for spotted owls, razorback suckers, or yellow-billed cuckoos might be adversely affected by activities like mining, the government will stop it in a heartbeat. Many Coloradans have tried in vain to get “incidental take” permits for their normal ongoing operations. But with this particular mine, owned by a Canadian firm, it’s no problem – even if it costs us the last remaining jaguar in the country.

The jaguar was listed as endangered in 1997, though many USFWS biologists maintained that the spotted felines were never really common in the U.S. They range from Argentina to the Rio Grande River, as always, and there are thought to be 20,000-30,000 of them today. But sometimes they crossed into the U.S. and their sightings around the southwest were not uncommon. Still, the government considered them a low priority and failed to designate “critical habitat” – the primary tool needed for enforcement actions – until forced to do so by a lawsuit in 2010. But within 3 years, the agency also issued its first “incidental take” permit, now revised and updated with the apparently insignificant fact that there is only one jaguar left.

So what were the endangered listing, incidental take permits, lawsuits, and critical habitat designations really about? If we are truly concerned about the fate of jaguars, we should study them, document them, understand their habitat, and keep tabs on their populations. But first, if we think they are in danger of extinction, wouldn’t we stop killing them? If we do not think they are in danger of extinction, so that “taking” them is OK, then why were they listed in the first place? That is the real question with so many species, and hardly anyone ever asks it.

There are two simple explanations for this apparent contradiction in policy. First, jaguars are not endangered. We should not confuse that reality with our sadness that they no longer occupy every inch of land they once did, or that their numbers may be smaller than originally. (We do not know that for sure, because no one knows how many there once were, nor how many once roamed the American southwest.) Second, the government knows the mine in question would not really hurt the jaguar, much less kill it.

The Rosemont Copper Mine, as proposed, would occupy about 955 acres of private land and 75 acres of state land. Because the designated critical habitat exceeds 850,000 acres spanning four counties in two states, USFWS concluded that the mine would not destroy habitat for jaguars, nor preclude migration throughout their habitat – if there were any jaguars there.

At least four federal agencies seek further involvement in this decision, along with five states and several Tribes. Rest assured, there will be lawsuits; this is not the final decision. That’s because the agenda is not about jaguars, it’s about controlling mining. The life of a particular animal, even the last American jaguar, is incidental. That’s just sad.

A version of this column originally appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel August 19, 2016.

Comments on this entry are closed.