Bees and honey have been important to my family for generations, though I’m not sure which is more important to us. My granddad was an apiarist (beekeeper), with hives in the high mountain clover of Garfield, Eagle and Routt Counties, and he made a living selling honey during the Depression and World War II. My parents and their Colorado orchards also depended on bees, more for pollination than for their honey. My brothers and I are still in the fruit and produce business, as dependent on bees as ever. We still sell honey, too – and eat plenty of it.

Bees and honey have been important to my family for generations, though I’m not sure which is more important to us. My granddad was an apiarist (beekeeper), with hives in the high mountain clover of Garfield, Eagle and Routt Counties, and he made a living selling honey during the Depression and World War II. My parents and their Colorado orchards also depended on bees, more for pollination than for their honey. My brothers and I are still in the fruit and produce business, as dependent on bees as ever. We still sell honey, too – and eat plenty of it.

It is ironic that with all the advances of modern science, mankind still has no more efficient way to pollinate the blossoms than nature, and mostly that means honeybees.

No wonder the reported decline in bee populations in recent years seemed so alarming, not only to farmers, but also to nutritionists, environmentalists, grocers, politicians, and regulators. The Nation’s Capital has been all abuzz about a syndrome called “colony collapse disorder,” with the usual approach – there ought to be a law. Clearly more regulation is needed, but what should we regulate? The cause of colony collapse remains unknown.

Now it turns out that the crisis may not be as bad as originally thought. Right in the middle of a new push to further restrict a number of pesticides and other agricultural chemicals, a researcher named Dr. Angela Logomasini published a study in Forbes concluding that such regulations may not only harm food production, but could actually be bad for the bees, too. That would sting.

Bees are so important, and the problem of beehive health so critical, that even the White House got involved. A year ago the President appointed a Pollinator Health Task Force, which released a “National Pollinator Health Strategy.” But Logomasini’s study found that much of the alarm over harm to honeybees by pesticides is not supported by facts. The number of honeybee hives, in fact, has increased around the world despite increases in pesticides, insecticides, and fertilizers. The losses by American beekeepers in recent years are more likely attributable to other challenges, she wrote, “mainly driven by natural forces such as the emergence and spread of diseases and parasites.” Experts including the White House panel have also identified the need for a more diverse diet in order to combat newer diseases.

Bees have, in fact, developed immunity to many of the most common agricultural chemicals (as many insects do), and have continued to thrive in heavily treated areas. There is significant danger, therefore, in banning currently used chemicals, because they will be replaced by new chemicals that may be more toxic to bees in the short term.

The most important management strategy for the bees and their hives, is also the oldest – close collaboration and cooperation between beekeepers and landowners. My granddad knew all the farmers on lands near his hives, and he knew what times of the year they used various insecticides. And of course they all knew there were hives nearby. In our own orchard, my wife and I always discussed the annual spraying with the beekeeper whose hives were on our property. He took action to protect them at crucial times, and we coordinated the schedule with him – because the bees were every bit as important to us as to their owner.

The use of agricultural chemicals has spread in recent generations, beyond the farms and into small gardens in towns and suburbs everywhere. That makes the traditional cooperation with beekeepers more difficult, since many homeowners are not even aware of the presence of nearby hives. Those are problems beekeepers are actively working on with homeowners and landowners. If all the committees, task forces, and blue ribbon panels writing reports on declining bee populations really want to help, they might focus some attention on backyard gardeners. Instead, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is moving in its usual wrong direction, deciding to limit new uses of neonicotinoids, a specific type of pesticide used by beekeepers.

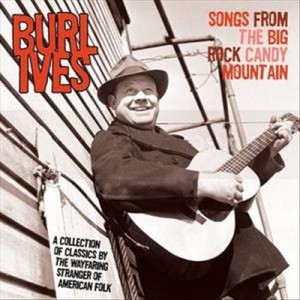

Some of these issues are as complex, and as poorly understood, as the honeycomb that bees seem to know instinctively how to build. Some issues simply do not lend themselves well to big government solutions. While regulators debate and argue, bees are recovering on their own, apparently unaware of all this activity on their behalf. So the buzzin’ of the bees will continue, in the cigarette trees, by the soda water fountain, where the lemonade springs and the bluebird sings, in the Big Rock Candy Mountain.

Some of these issues are as complex, and as poorly understood, as the honeycomb that bees seem to know instinctively how to build. Some issues simply do not lend themselves well to big government solutions. While regulators debate and argue, bees are recovering on their own, apparently unaware of all this activity on their behalf. So the buzzin’ of the bees will continue, in the cigarette trees, by the soda water fountain, where the lemonade springs and the bluebird sings, in the Big Rock Candy Mountain.

(A version of this column originally appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel March 11, 2016)

Comments on this entry are closed.