Like many westerners who deal with water issues, I have often found myself explaining our complex system of water laws, which seem bizarre in parts of the country where it rains all the time. People in such places (like Washington, D.C.) have trouble understanding why the right to use water is considered property, why someone would need to “own” water, and especially why even land itself may be worthless without “water rights.”

We explain the simple impossibility of living in the arid West without the ability to take water out of the river and put it to use. Since that is true nearly everywhere, it’s the easy part of the dialogue. The disconnect occurs when describing the concept of “prior appropriation.” It’s simple enough – if a person diverts water from a natural stream and puts it to beneficial use, he acquires a property right. The only major exception is if someone else was there first. Because no western stream contains enough water for every future need, special courts “appropriate” the water to specific users, based on the “priority” of who was there first. This “doctrine of prior appropriation” is unique to the arid West, which simply could not have become home to millions of Americans without it.

I have always admired the early pioneers who designed this complex legal system, based on older Mexican law that existed before these territories became part of the U.S. But I little understood how much older those concepts really are.

It began to crystalize for me while reading a classic 1868 book called “Life Among the Apaches.” The work has long been noted among historians because its author, Major John Cremony, had such a unique opportunity to get to know the Apache tribes and leaders, first as interpreter to the U.S. Boundary Commission in the 1840s, then as a Cavalry officer in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas during the Civil War. He was the first white man to become fluent in the Apache language, and published the first written compilation of it. He met the Apaches first as an enemy, but became their greatest advocate (almost like “Dances With Wolves”). Cremony grew to understand why these tribes viewed white settlers with such alarm, and believe it or not, it was more about their water rights than anything else.“The Apaches entertain the greatest possible dread of our discoveries of mineral wealth in their country,” Cremony wrote. But not because they attached any particular significance to the value of the mineral ore – they found the Americans’ obsession with gold and silver comical. Rather, it was about the water. “The occupation of mines involves the possession of water facilities… To occupy a water privilege in Arizona and New Mexico is tantamount to driving the Indians from their most cherished possessions, and infuriates them to the utmost extent. If one deprives them of their ill-gained plunder he is regarded as an outrageous robber; but should he seize upon one of their few water springs, he is rated a common and dangerous enemy, whose destruction is the duty of all the tribe.”

What an eye opening insight. We should have always instinctively known that the native people were as dependent on, and therefore attached to, water rights as the new settlers. It turns out that attachment to water – in the same direct legal sense in which we think of it today – was notable throughout the West, including among the Ute tribes that occupied much of what became Colorado and Utah.

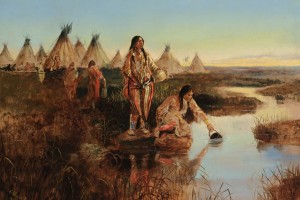

One band of Northern Utes called themselves Pahvant, which meant “living near the water,” a description not only of their geographical location near the Wasatch mountains, but their way of life, connected to the water economically, historically, and culturally.

The same was true on the Western Slope, where the Weminuche Utes inhabited the Dolores and San Juan watersheds, and the Tabeguache Utes occupied the Uncompahgre and Gunnison. Other Ute bands were located in, and named for, the valleys of the Grand, White, and Yampa Rivers. Their lives and livelihoods were inextricably linked to the river systems they inhabited, and like the Apaches, any incursions that threatened their water threatened their survival. They suddenly had to contend with outsiders who not only wanted to live on the land, but to do so, needed to establish a legal system of ownership over the water.

We’ve often smiled at Mark Twain’s famous maxim that “whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting.” Apparently the West’s white settlers did not invent that reality.

(A version of this column originally appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel February 5, 2016)

Comments on this entry are closed.