Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s death sparks another political battle over the high court, whose balance of power hangs on one vote. Several vitally important rulings have recently been decided by a 5-4 majority, so battle lines are already drawn. President Obama sees a chance to turn the court into a liberal majority, and Republican senators are determined that he must not be allowed to do so.

The Constitution only says that the President “shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint… Judges of the Supreme Court.” In today’s context, that means two things: this President is clearly entitled to nominate a new Justice to replace Scalia, and this Senate has no obligation to consent to it. But for what reason would the Senate refuse to do so?

The Constitution only says that the President “shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint… Judges of the Supreme Court.” In today’s context, that means two things: this President is clearly entitled to nominate a new Justice to replace Scalia, and this Senate has no obligation to consent to it. But for what reason would the Senate refuse to do so?

From the beginning, it has been clear that a President has the right to nominate whomever he chooses – and is not required to explain his reasons for the choice. Nor has the Senate ever been required to explain its reasons for confirming or rejecting nominees. Senators can reject a nominee for any reason they think appropriate, as they have often done. The Senate has declined to confirm almost 25 percent of all Supreme Court nominees, several times without ever voting.

Supreme Court nominees always attract much more scrutiny than lower court nominees, even though the latter also serve for life. That’s partly because there are 865 judges in the lower courts and only 9 on the Supreme Court, and partly because Presidents often defer to senators’ recommendations for lower court appointments in their states. But it’s mostly because lower court judges have far less power – they are more constrained by Supreme Court precedents, and they don’t get the last word. Supreme Court nominees, though, have enormous power.

Still, for the Senate Majority Leader to announce in advance, as Mitch McConnell (R-KY) did last week, that the Senate will not even consider any appointment from this President, sounds unseemly. It is true that when the situation was almost exactly reversed, Democratic leaders in the Senate also publicly said President Bush should not nominate another Justice before his term ended. But it sounded like cheap politics then – and it sounds the same now. There is no doubt Senators will again be called partisan obstructionists, but they could prevail without that appearance.

To most of us, it would sound better for Senators simply to say they will not vote to confirm another liberal who would change the direction of the court and interpret the Constitution in new ways. They are entirely free to vote for that reason, and most of us would accept it at face value because it would be the honest truth.

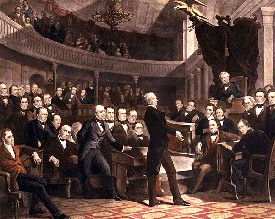

Here is something else such a clear criteria would be – advice to the President while he is considering who to nominate. Why does the Constitution say “advice and consent,” if it only means “consent?” Over a long period of time, the terms have merged into one process, whereby the Senate simply confirms an appointment or rejects it. But it wasn’t always clear that the Senate had to wait for a nominee, and then could only vote yes or no.

The Senate’s first rejection of a nominee came barely four months into George Washington’s term as President, and it provoked a tactful letter from him helping define the Senate’s role. He actually told senators he would have appreciated knowing in advance any concerns they might have, so he could share his reasoning with them and they could work together to resolve it.

There were differing opinions on whether the Senate should advise the President before a nomination had been made, but nobody ever suggested it could not do so. We know James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and John Jay all advised Washington that he need not consult the Senate before making nominations. Roger Sherman thought differently, and explained in a letter to John Adams that the advice of Senators’ in advance would enable a President to make better appointments. Indeed, Presidents often consult informally with senators over nominations, so what would be wrong with formalizing that, especially in a year when the balance of power is so delicate?

Rather than wait for Obama to nominate someone senators cannot support, perhaps they should send him a list of nominees they can. That would get ahead of the criticism they are certain to endure otherwise, and would exercise their power not only to “consent,” but also to “advise.”

(A version of this column originally appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel February 26, 2016)

Comments on this entry are closed.