During former President Theodore Roosevelt’s independent campaign of 1912, he famously referred to incumbent President William Howard Taft as a “puzzlewit.” The self-defining term is a rarely-used but creative and entertaining word for someone stupid. It provoked Taft, who responded by calling Roosevelt a “honeyfuggler.” That’s worse. It describes a swindler who plots to deceive and cheat others.

Every election year people love to complain about all the negativity and mudslinging. We already hear the same complaints this time – and it isn’t even an election year yet (the campaigns do seem to start earlier). When I once ran for office people got so angry that a few even told me and my opponent (we compared notes afterwards) that if they heard one more negative ad they would refuse to vote for anyone.

Every election year people love to complain about all the negativity and mudslinging. We already hear the same complaints this time – and it isn’t even an election year yet (the campaigns do seem to start earlier). When I once ran for office people got so angry that a few even told me and my opponent (we compared notes afterwards) that if they heard one more negative ad they would refuse to vote for anyone.

Some observers thought the nastiness reached a feverish pitch when one side accused Mitt Romney of being a “vulture capitalist” and other questioned President Obama’s religion, as well as his birth certificate. This year, mentioning the Hillary Clinton scandals, Donald Trump’s hair, Bernie Sanders’ socialism, and Carli Fiorina’s layoffs at HP, I already heard one major national commentator express the view that the ugliness of campaigns may be the worst in history. As if questioning someone’s honesty, experience, or opinions on important issues should be off limits in a civilized campaign.

In fact, today’s campaigns are exceedingly civil, downright mild compared to those of America’s earlier years. The first really contested national election was in 1800 and right from the start the two sides went at it hammer and tong. Adams supporters published scurrilous rumors of Jefferson’s private life (matters on which history is still uncertain), said he would cause a civil war, and was an atheist. Jefferson’s campaign made fun of Adams’s supposed sympathy for the monarchy, and his weight problem, mockingly calling him “his rotundity,” in addition to old, querulous, bald, blind, crippled, and toothless! It took the two men years to get over the bitterness left behind by the split, though aggressive partisans today demonstrate that the country never fully got over it.

Within a few short years, campaigners were accusing Martin Van Buren of wearing women’s corsets to hide his gut, claiming John Quincy Adams was a pimp who provided prostitutes for Russian officials, Abraham Lincoln had smelly feet, James Buchanan had tried to hang himself, and Andrew Jackson was a cannibal who breakfasted on dead Indians.

It was Jackson, not Obama, whose parentage and personal history was first openly questioned in campaigns. Jackson opponents claimed he was born in secret of a mixed-race father and a British prostitute mother. Hillary Clinton is sometimes accused of a negligent response to the Ben-Gazi incident, but Jackson was accused of enjoying the thrill of personally shooting American soldiers (deserters). Donald Trump refers to Jeb Bush as “low energy,” and implied that Fiorina was too ugly to be President. But FDR referred to his 1936 opponent, Alf Landon, as “the white mouse who wants to live in the White House.” Nor was Bill Clinton the first President accused of infidelity. “Ma, ma, where’s my pa? Gone to the White House, ha ha ha!” referred to Grover Cleveland in 1884, and similar rumors plagued the campaigns of Warren Harding, John Kennedy, and several others.

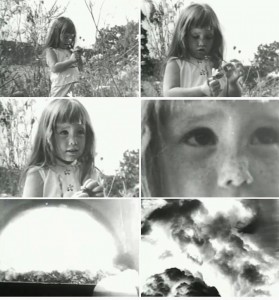

Television allowed several even more dramatic moments, such as the 1964 “Daisy Girl” ad, in which Lyndon Johnson implied that if Barry Goldwater were elected the Russians would drop an atom bomb on your children. Some candidates have been called too soft, or not tough enough to stand up to foreign threats (as was said of Franklin Pierce, Woodrow Wilson, Jimmy Carter, and Bill Clinton). Others are said to be loose cannons who will get us into war (Jackson, Goldwater, and Ronald Reagan).

Today these kinds of campaign rumors are more likely to circulate on the Internet. One website masqueraded as an official Fred Thompson site, but was in fact designed to embarrass him. The Internet can quickly spread viral “news” like 2000’s Photo-shopped picture of Jane Fonda and John Kerry. The tools have changed, but not the tone.

Thomas Elder wrote in 1840 that “Passion and prejudice, properly aroused and directed, do about as well as principle and reason in any party contest.” Most Americans wish the level of public discourse was loftier. They yearn for a time when candidates engage only in thoughtful debate about important issues. But that is not nostalgia. It is a hope for something that never was.

Comments on this entry are closed.