It is a little unusual for national newspapers to cover western water issues, but in August the Wall Street Journal ran a story about the year-long struggle over water rights proposed by the City of Glenwood Springs. The article was predictably superficial, but called national attention to something Western Slope residents understand to the core of their DNA – Front-range water providers always, always have their eye on the Colorado River.

At the heart of this dispute is an application by the City for water rights, not for drinking or irrigating, but to be left in the stream for rafts and kayaks. If successful, the application would effectively prevent almost any future uses on the Front Range (which already diverts roughly half of the Colorado River across the Continental Divide).Colorado has a strong and active program to preserve instream flows to preserve existing stream conditions or to restore native flows. Such instream flow rights can only be held by the State, filed and managed by the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB), but it is limited to flows that preserve environmental values, not economic values.

This case is interesting precisely because it is about the economy, not the environment. Glenwood Springs sees millions in revenues every year from recreational use of the River. If future diversions to the Front Range deplete the River to the point that it cannot support such recreation, it could devastate a community more dependent on tourism revenue than ever before.

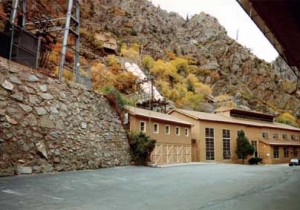

That has not happened so far, largely for one reason – the little hydro-electric power plant in the middle of Glenwood Canyon. The Shoshone Plant operates with a water right that dates from 1902. At 1,250 cubic-feet per second, it is the largest and one of the oldest water rights on the Colorado River, senior to all trans-mountain diversions, including Denver, Aurora, and Colorado Springs. So as long as that power plant operates, there will always be enough water in the River to make Glenwood Canyon one of the nation’s finest rafting and kayaking experiences.

Can Western Slope communities count on the power plant always to be there? Owned by Xcel Energy and its predecessors from the beginning, the plant is well over 100 years old, and Xcel spends millions keeping it operating (such as $12 million on repairs following a 2007 breakdown). For years, there have been rumors that Denver wanted to buy the plant and its associated water right in order to shut it down, and there have been various efforts by West Slope entities to buy it in order to keep it going. Naturally.

Glenwood Springs is simply trying to get ahead of the curve, and file on water rights of the same quantity in case the plant is ever sold or shut down. Logical enough, because Glenwood has a massive water recreation economy to protect. But in early July, the CWCB voted almost unanimously to recommend that the water court deny Glenwood’s application. The reason getting such water rights is so difficult is a great primer on why Colorado water law is the way it is.

The original constitutional water law was fairly simple: if you divert water from a stream and put it to beneficial use (drinking, farming, or mining), you acquire a property right and cannot be stopped. Only one exception, if someone else was there first. That’s complex Colorado water law in a nutshell. People’s use of water over the decades expended beyond the original limited purposes, of course, so the instream flow rights program was added and today the CWCB has protected almost a third of the stream miles in the State, and 486 natural lakes.

In 2001 when I was Director of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources, we convinced the Legislature that there were economic interests in preserving instream flows, not just environmental interests. Thus, “recreational in-channel diversions” were created, to be used exactly the way Glenwood proposes. However, such new rights cannot hinder Colorado’s ability to develop all the water to which it is entitled by Interstate Compacts.

That is why the CWCB’s approval is all but mandatory, and it is a prerequisite that CWCB could not get around in this particular case. But Glenwood won’t quit trying, and shouldn’t.

Mark Twain famously wrote that in the West, “whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting.” That is truer now than ever, because water is worth money, both when it’s diverted out of the river – and when it’s left in.

(A version of this column originally appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel August 28, 2015)

Comments on this entry are closed.