Yesterday I testified before an unusual committee in Congress, one with a membership made up almost entirely of westerners, and in particular westerners whose districts are mostly federal land. That is unique in Congress because rural westerners are a small minority. They normally have trouble explaining to their colleagues the nuances of public lands and water issues.

This new coalition is called the Federal Land Action Group, chaired by Utah Congressman Chris Stewart and with several other Members from Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, and Nevada. Its purpose is to examine better ways to manage the public lands, perhaps by the states. As I told the committee at yesterday’s hearing, there has never been a better time for that discussion.

There is often a false assumption about the manner of federal acquisition of these lands in the first place. The U.S. government paid just over $55 million for the entire Western United States – a third of the annual budget of the City of Grand Junction, and an average of less than 10 cents an acre. Then to encourage settlement of the West, the government gave away or sold this land to homesteaders, railroads and new states. That was always the intent. The federal government never had any intention of owning and perpetually managing public lands. So any modern thought that the United States has a major investment in these lands is simply a bad reading of history.The primary goal for public lands throughout that era was to convince Americans to settle it, own and occupy it, and turn it into productive and prosperous new states. The strategy worked to a degree, but most of the West was never privatized – because people settled land that was best to farm and nearest to water. They settled the valleys and left the mountains and deserts alone. Those remained in federal ownership for one and only one reason – no one else wanted it.

That is the primary reason a provision promising transfer of those lands to the states was included in the original statehood acts of all the new states. Privatization was taking longer than expected, so the new states could continue that effort without having to wait for statehood. Yet in States east of the Mississippi that promise was kept, and in nearly every western State it was not.

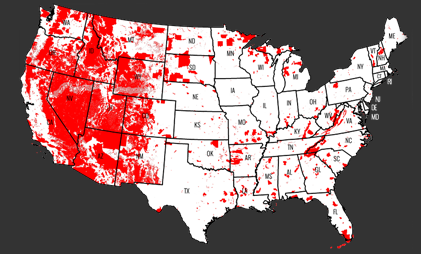

That created a convoluted checkerboard of land ownership that dominates the West, surrounding nearly every community with federal lands and the U.S. government as the largest landowner. It eliminates most of the local tax base, gives federal managers undue influence in local communities, and fuels endless disputes about management of those lands.

One overpowering argument should be at the heart of this discussion: the government cannot responsibly manage the 650 million acres it now owns. Efforts to balance energy production with environmental protection have utterly failed, leaving America dependent on imported oil and contributing to global instability. And the Forest Service now classifies more than 60% of all the trees in our national forests as unhealthy, diseased, dead or dying. Over the past ten years, wildfires have ravaged 68 million acres of these prized forests, a direct result of mismanagement.

That is why some committee Members are examining possible approaches to state and local management, or a combination of federal and state management. It is worth considering.

Some argue that states couldn’t afford the high cost of management, or that states would abuse the public lands if given the chance. Both arguments are demonstrably false. First, the current outrageously-high cost of federal land management is neither inevitable nor necessary. States would not only spend less, but would probably make money. Second, the view that states would turn over public lands to abuse and destruction is not only insulting to people who care passionately about their environments, but also ignores the reality of federal land management today. It is the latter that is proving to be a death sentence for the nation’s forests, wildlife, and other resources. The generations of westerners who grew up and live in these special places not only know them best, they love them most.

The time is right for a new discussion of how we care for public lands. Crushing federal debt, and ineffective environmental stewardship, afford Congress an opportunity to consider a new approach with substantially more state and local involvement – not just input, but actual decision-making authority. That would not only help reduce the federal budget, it would be better for the environment.

(A version of this column originally appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel July 31, 2015)

The American Energy Alliance Opposed The CAFE Standard Agreement The Obama Administration Reached With Car Companies. “The White House announced yersdteay that the Obama Administration has collaborated with GM, Chrysler, Ford, Honda, and Hyundai to increase Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards for new cars to 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025.a0 While studies have shown that this standard will have no impact on global emissions, it will increase the profits of the endorsing companies by forcing Americans to buy more expensive cars. In response, Thomas Pyle, president of the American Energy Alliance, issued the following statement: ‘Yesterday’s CAFE announcement is government intervention at its worst. a0Higher fuel economy mandates are based on the Obama Administration’s belief that Americans are too stupid to decide for themselves which cars to buy.a0 The auto companies should be ashamed of themselves for rolling over, yet again, and signing on to this pact.’” [American Energy Alliance, 7/29/11]

Comments on this entry are closed.