I speak and write often about policies that limit public access to public lands, because I worry about a giant philosophical divide, based on the theory that mankind’s presence is always bad for the environment. People are not part of the environment in this theory. They are an intrusion that should be stopped whenever possible. The idea is relatively new, and contradicts one of the most important themes of the original conservation movement: justice.

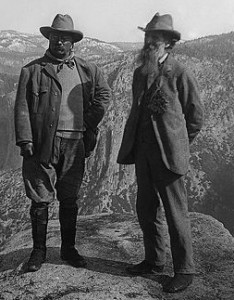

The early writings of Theodore Roosevelt and other conservation pioneers contained three essential concepts. First, resources must be used wisely to supply the needs of a growing economy. Second, resources must be renewed and preserved so they will still be available for future generations. The conflict between those two notions forms the basis for most environmental arguments today. But there was a third essential concept, nearly lost in the modern debate, that resources must be available equally to all people, not held as the province of an elite few. Gifford Pinchot captured all three ideas in his simple slogan for national forest management: “the greatest good for the greatest number over the greatest time.”The three points are unquestionably interconnected. Forests could provide the greatest good for the current generation by being completely cut, providing cheap wood and paper, but that would be a disaster for the future. Conversely, forests could be entirely saved for future generations, guaranteeing they would last for the greatest time, though the lack of any wood or paper would be an economic disaster today. Finally, providing total control of the forest resources to corporate interests might maximize profits, but would not provide the resources for the greatest number. And freeing the rest of society from the control of Gilded Age “robber barons” was central to Roosevelt’s progressive movement.

The wisdom of this equation has never changed. We should not over-utilize natural resources for the sole benefit of today’s generation, with no thought about the future. Nor should we fail to use these lands to provide vital resources we need today (such as energy). Neither should we allow an elite few to be sole beneficiary of resources that belong to all the people.

Activists who want to lock up public lands against the multiple uses for which they were created are much like those who once sought to own and control the entire nation’s timber and mineral supplies. Are these latter day elitists any different than history’s robber barons in pushing land policies that benefit only one segment? Our ancestors fought a revolution against the concept that all resources belonged to the crown and peasants could be executed for killing the king’s deer. Yet today we deal constantly with the notion that public lands should only be used by a few people for permitted purposes, and federal land agencies treat these resources as if they must be protected – not for the public, but from the public.

Today’s leaders have actually forgotten the concept of environmental justice. The resources belong to all of us, not just those who want to hike and be alone. The solitude of a national forest and the thrill of hooking a wild trout belong equally to people confined to wheelchairs, or elderly people no longer able to hike two miles to their favorite lake. A nation desperate for energy independence is entitled to use energy resources the public owns.

Many environmental groups still use the term “environmental justice,” though they misconstrue its meaning. To them it means the forests do not belong to timber interests, or that oil shale lands belong to hikers as much as to oil and gas companies. They are right about that, of course. But they use the concept to build figurative walls around vast tracts of public spaces, no longer available to millions for any purpose. That’s why well-meaning environmental laws are so often used, not to protect endangered species or to clean up air and water, but to restrict human activity. That represents the opposite of environmental justice. That is today’s aristocracy, using immense sums of money and power to control the nation’s natural resources for its own exclusive benefit. The greatest good, over the greatest time, but only for some people.

These resources belong to all the people who will come after us, but also to the people alive today. Public resources belong to ALL, not just loggers and drillers, not just ranchers and hunters, and not just hikers and photographers.

(A version of this column appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel June 1, 2015)

Comments on this entry are closed.