There is an impassioned conversation inside the Beltway lately about massive investments in liquefied natural gas (LNG) around the world, while several such projects in the U.S. have been abandoned or put on hold. Part of that conversation is about how different European politics and economics would be if the major energy supplier were the United States, rather than Russia or the Middle East.

More than once in the last few years we have seen companies whose proposals held great promise for the future of our country abandon those projects because it was – quite simply – easier, faster, and cheaper to build them somewhere else.

Despite even these setbacks, the United States is quickly becoming the world’s largest producer of natural gas, with new discoveries and modern technologies making previously unknown reserves available and profitable.

Despite even these setbacks, the United States is quickly becoming the world’s largest producer of natural gas, with new discoveries and modern technologies making previously unknown reserves available and profitable.

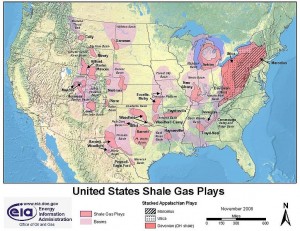

The massive discoveries in the Marcellus and Bakken formations, among many others, make it clear that American dependence on foreign energy is no longer necessary. We now know that there is more oil (at least 20 billion barrels) under North Dakota alone than the Energy Department thought were the entire U.S. reserves just 14 years ago. And our recoverable natural gas is even more impressive. The Marcellus formation in the northeast probably contains at least 2 decades of supply for the entire nation, even at today’s high consumption rate. Turning such gas into liquid makes it exportable, and offers a real prospect of changing energy-driven world economics, and politics.

Global competition can be a pesky thing, though, and not all countries play by the same rules. Americans care passionately about the environment and have erected all sorts of regulatory hurdles designed to protect it. Sometimes those regulations and permitting systems result in a very lengthy process, often followed by delays, appeals, lawsuits, more delays, and endless frustration. Most importantly, they can result in dramatic increases in the cost of completed projects. Energy economics are tight, and even slight changes in the cost of projects, or the price of commodities, can make or break a project’s viability. We should always consider carefully whether that’s what we really intended.

Consider the gas-to-liquids facility Shell had proposed building on the Mississippi River last year. Millions of dollars were invested; a site was selected with great fanfare; local governments were excited about the coming jobs and tax base; energy economists were predicting significant shifts in markets; and the permitting process was well underway. But in the final analysis – despite the huge investment already made – Shell determined that its investments elsewhere were more certain, and pulled the plug. The company had been forced into a similar conclusion on its oil shale investments in Colorado, after a decade of very expensive research, at least partly because the Interior Department decided to slow down development of that resource and the permitting process was daunting (most of those resources are on public lands).

An appeals court ruling this month may have finally cleared another legal hurdle for the same company’s operations off the Alaska shore – but the future there remains unclear. It is widely reported that more than $5 billion has been invested in those leases since 2000, without a single successful well being completed, because of the legal delays. During that same time, the same company has drilled more than 400 new wells elsewhere.

While the debate rages in the U.S. about what, if anything, should be done with domestic energy resources, other countries similarly endowed with mineral riches are moving ahead with deliberate speed. Since 1990 Qatar, for instance, has become the world’s largest producer of liquid gas. Shell spent $21 billion building a LNG plant at Ras Laffan and another called the Pearl, the world’s largest gas-to-liquids plant. It turns natural gas into 140,000 barrels of liquid fuels a day, and a company official there refers to Qatar as “the new heartland.” Several other major oil companies have similar investments there. Qatar now boasts 14 LNG plants, capable of producing 77 million tons of fuel each year. And that industry has given Qatar the highest per capita GDP in the world.

Energy companies have also found investing in Russia profitable. One has now entered into an agreement with President Vladimir Putin to expand a LNG plant on Sakhalin Island – a 50 percent expansion (from 10 million metric tons to 15 million) that may net as much as $4 billion for Russia in the first year alone. It also offers Putin access to Asian markets for Russian energy, in addition to the European markets he already dominates.

Though a couple of these examples are about Shell, the same experiences are shared by nearly every major energy company. The projects in Qatar and Russia did not require lengthy environment impact statements, no public comment periods, no appeals by environmental organizations, no court orders remanding any permit to any agency for review – just a go-ahead decision from one guy. That is an advantage for Russia, Qatar, and other countries ruled by dictators or monarchs. It’s an advantage with which America will never compete (nor should we) because as Alexander Hamilton summed it up, “Here, sir, the people govern.”

Like it or not, our almost-uniquely American concern about the environment is both a curse and a blessing. Keep in mind that despite the apparent hurdles to large projects in this country, our energy production is dramatically increasing – in environmentally responsible and sustainable ways that we can all feel proud of. And our grandchildren will be proud that we cared enough to get it right. Will Putin’s grandchildren?

I frequently counsel clients not to lose heart. America’s cumbersome process may seem daunting, but we can help companies navigate that process successfully. It can be done, and done right – and it should be. There is a sense of accomplishment, as well as profit, in doing so.

Comments on this entry are closed.