“Equal justice under law” is more than a quaint expression engraved on the portico of the Supreme Court building. It is a worldview that is central to our American culture. It is also a cornerstone of the conservation movement, but you wouldn’t know it by watching the angry activists that form so much of the modern environmental lobby.

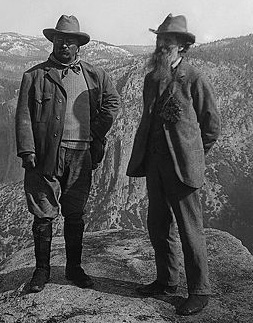

The founders of the nation’s first great conservation movement – Theodore Roosevelt, John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, John Wesley Powell, and others – pioneered the notion of “environmental justice,” but it’s not what you think. That’s because the term is so commonly abused by the POE’s (people opposed to everything). In their oft-stated view of “environmental justice,” it seems the concept requires that we lock up public lands from the public, stop the production of energy, live in smaller homes and quit traveling. We have to scale back our lifestyle, they argue, because our use of the planet Earth is destroying it. To these organizations, environmental justice means the natural resources have rights just as important as our own and must be protected – from us.

The founders of the nation’s first great conservation movement – Theodore Roosevelt, John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, John Wesley Powell, and others – pioneered the notion of “environmental justice,” but it’s not what you think. That’s because the term is so commonly abused by the POE’s (people opposed to everything). In their oft-stated view of “environmental justice,” it seems the concept requires that we lock up public lands from the public, stop the production of energy, live in smaller homes and quit traveling. We have to scale back our lifestyle, they argue, because our use of the planet Earth is destroying it. To these organizations, environmental justice means the natural resources have rights just as important as our own and must be protected – from us.

That is almost exactly opposite of what Roosevelt and the other early conservationists intended.

The progressives of the last century who created national parks and national forests did so for three primary purposes. First, these lands supplied the natural resources necessary to build a prosperous society, including lumber, water, minerals and recreation. Second, the use of such resources must be monitored and regulated to ensure they are also available to future generations. Those first two purposes are to this day the basis of the divisive – and litigious – nature of environmental disputes. But there was a third purpose, too, found throughout the writings, lectures and letters of Roosevelt and the others. That purpose was to ensure that these resources belong to everyone, not just one segment of the society.

The trees in national forests do not belong just to timber companies, nor minerals on public lands only to mining companies, but to everyone, they argued. Similarly, public lands are open to everyone, not just the ranchers with grazing permits. Believe it or not, this theory was highly contentious at the time. Perhaps we need that debate again.

Today’s environmental lobby would close most public lands to all but the hearty few able to walk there and lucky enough to live nearby. They would allow the national forests – one of the greatest legacies of the early conservationists – to die and burn before allowing anyone to cut a tree. And they would lock up all our energy resources, perpetuating our dependence on foreign oil. In their view, America’s resources may belong to everyone, but not everyone gets a seat at the decision-making table. Those who seek preservation for the future – without any use by our generation – are more in charge of the debate than ever. But do public resources belong only to environmentalists? That view may seem like “equal justice under law,” but only if you think some of us are more equal than others.

I disagree with you about accessibility. As one who has explored much of the Western United States and hiked in many of the national forests I believe these lands should remain a challenge to all. Keep it wild.

Somewhere someone forgot all about managing public lands for the”greatest good for the greatest number” Gifford Pinchot thought it ws important.

Comments on this entry are closed.