Americans love the idea of the wild horses, more than we love the animals themselves. That’s why wild horses in the West are among the most controversial issues perennially facing the BLM. There are at least 70,000 horses running wild in the West, and 50,000 more in BLM holding pens. The agency spends upwards of $87 million annually trying to manage wild horses, but it is a losing battle. The number of horses doubles every four years, and the BLM cannot even give them away. They round up 3,000 or more every year to reduce herd size, but only a fraction of those are ever adopted (111 last year) and many are euthanized or sold to rendering plants.

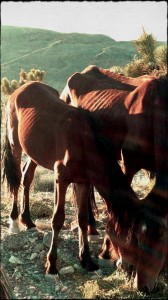

If that last detail sounds unsettling, hold your horses for a minute. The problem with these herds of wild horses is that they decimate rangeland ecosystems that are also vital to native wildlife, particularly deer and elk. In some places, grazing cattle also compete for the same forage, but in several areas where cattle were removed from the range a decade ago, the landscape remains barren because of the horses. The latter are often desperately hungry and eat anything left. Many starve to death every year, so the situation is unsustainable, for the environment and especially for the horses. A National Wild Horse & Burro Advisory Board helps determine the land’s “carrying capacity,” and the number of horses that should be culled annually. Some members consider the situation an emergency.The 1971 law governing BLM’s wild horse management allows removal of excess horses from the range, selling them at cost, and euthanizing aging or sick horses. At a recent meeting of the Advisory Board, a strong recommendation to do exactly those things shocked and horrified some observers, and greatly relieved others.

Almost immediately, as reported in Range Magazine, “horse activists implemented their public relations machine, social media lit on fire, emails flew through the ether, and all hope of saving public lands, the fragile ecosystems, the customs of multiple use, economies, and private property rights disintegrated behind cries to ‘save the horses.’” Such emotion is misplaced.

The term “wild horse” is a misunderstanding. They are more accurately understood as escaped horses. The tradition is that they descended from horses that escaped hundreds of years ago from Spanish conquistadors. In fact, nearly all of them descend from horses that escaped much more recently. A few horses, for instance, released during the Depression by a DeBeque rancher who could not afford to feed them, are the ancestors of many horses now roaming the Western Slope.

The horses’ ancestry is controversial, because horses were once native to the West. Fossil remains prove that they migrated to Asia and Europe from North America, about the same time the first humans migrated the other direction, 2-3 million years ago. Those ancient American horses went extinct about 12,000 years ago. There have been several other sub-species of horses, zebras, and donkeys over the millennia, most of them now extinct, and it remains a topic of discussion among paleontologists how different the modern horse is from the Yukon horse last known in North America.

One recent study questions whether there is any difference at all, but most scientists, and government policies, rely on the conclusions of many studies over the past 50 years of numerous ancient animal species that are now extinct. Wildlife officials are supposed to do what they can to protect and preserve native species, and they generally do a good job. But the BLM herds are a horse of a different color. They are not native, they destroy habitat, and they are not thriving. Elimination might be the most humane solution.

Most of us dislike cruelty to animals. More than once I heard my Grandma express the opinion that all men were destined for hell because of the way they treated horses. Surely, we can do better for these poor animals than leave them in the desert to starve.

A version of this column originally appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel April 21, 2017.

Comments on this entry are closed.