America’s most influential liberal think tank just published a report advocating reversal of decades-old environmental mitigation policy. It calls for mitigation not by those responsible, but simply by those with deep enough pockets.

America’s most influential liberal think tank just published a report advocating reversal of decades-old environmental mitigation policy. It calls for mitigation not by those responsible, but simply by those with deep enough pockets.

The plan suggests that organizations proposing new projects must first pay for cleaning up messes left by others. More euphemistically, the report calls for “a series of pilot projects to encourage abandoned mine cleanups and dam removals and to offset the environmental harm of fossil fuel production.” “Encourage” is the understatement of the year. It means federal officials would require such actions as a condition of permits for mining, drilling, water development, manufacturing, timber harvesting, pipelines, refineries, power plants, and any number of other projects.

The report was written by the Center for American Progress (CAP), founded by former top Clinton aides. The organization has served as author of nearly all major initiatives of the Obama Administration, and as a revolving door for White House staff and campaign operatives. Its reports often provide the philosophical underpinnings for policies on the liberal “wish list.”

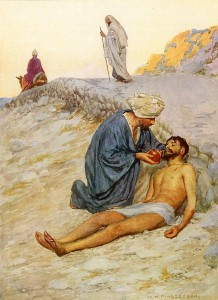

This mitigation scheme has been on that wish list for years. It also runs exactly counter to a growing movement known as “Good Samaritan” legislation. The latter recognizes that such projects create jobs and supply needed products and services, but for the environmental liability companies risk when operating on previously occupied land. For instance, reopening an abandoned mine or repurposing a former power plant, a new owner might be required first to clean up old chemicals leached into the ground by previous owners – even if the previous hazard is only discovered years later. That risk has discouraged countless projects over the years.

Under current law, liability remains with companies at fault, as it should. But often, those companies no longer exist, so the liability may stay with new owners. Companies are frequently at risk of lawsuits, demanding they pay to clean up some problem they had nothing to do with. Proposed “Good Samaritan” legislation would exempt new owners from liability if they perform the cleanup. It has been introduced annually since 1999 by Senators of both parties, including Democrats like Max Baucus and Mark Udall.

Despite growing consensus, the environmental lobby has always killed the idea. They fear that letting new landowners off the hook for previous landowners’ actions might leave government responsible for the cleanup. That is precisely where the responsibility should lie. If the public wants old pollution cleaned up, the public ought to pay, not shift the burden onto a private owner who was not responsible, but who nevertheless steps forward to clean it up. Good Samaritan legislation seems likely to pass in the near future.

The issue resurfaces with every major catastrophe like the Gold King mine spill that poisoned the Animas River. Congressional hearings on that EPA fiasco again focused on Good Samaritan. EPA was only involved because the original mine owners were long gone. But absent such legislation, huge liability would have followed anyone else trying to clean it up.

With a steadily emerging majority on Good Samaritan legislation, opponents are fighting back. The CAP report goes far beyond the traditional system, calling for “no net loss” of natural resources. Instead, it advocates a permit requiring a “net gain” for all actions on public lands (private lands to follow soon). Thus, new projects would be expected not only to clean up someone else’s mess, but to positively “improve” the environment before being permitted.

Proposed “pilot projects” might include “mitigation credits” awarded to “environmental remediation firms that clean up abandoned mines to gain mitigation credits.” Note that the credits would be for environmental firms, not mining companies. The report explains that “These firms could then sell the credits to mining companies,” which would of course be required to purchase them to “compensate” for their own mining. Ditto for oil and gas, oil shale or coal leasing. Coal mines would have to pay a “climate mitigation fee,” perhaps to the same environmental remediation firms. Water districts could earn similar credits for tearing down dams, but might be denied permits for improvements unless they did so.

Mitigation banking is not new, of course. But this new report makes it seem less likely that companies could do their own cleanup work and earn mitigation credits, and more likely they would have to buy those credits from environmental firms favored by the government. That sounds more like a financial scheme to pick winners and losers than a real plan to clean up pollution.

A version of this column originally appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel November 4, 2016.

Comments on this entry are closed.