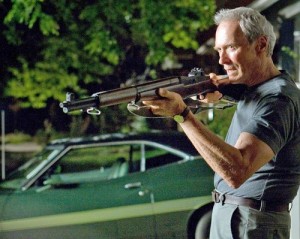

There was a time when the rules of congressional courtesy forbid congressmen from introducing bills affecting another congressman’s district without a very specific agreement between the two. The standard was simple: “you take care of your district and I’ll take care of mine.” There was a strong sense of “turf” that all Members respected, almost as sacred as private property. Trespassing on someone else’s lawn was about the same thing as trespassing on the “turf” of a Congressman by introducing legislation affecting his district. And he might react as angrily as Clint Eastwood in “Gran Torino,” who was moved to bring out his old M-1 rifle to force the neighborhood thugs off his property.

When Wayne Aspinall chaired the House Interior Committee, Members from Massachusetts did not introduce bills changing the management of public lands in Utah. Today it is common. Many courtesies of civil government have disappeared in Washington, but this one is especially disturbing to Westerners, who can’t just get out the shotgun to defend their turf. This is not the movies.

When Wayne Aspinall chaired the House Interior Committee, Members from Massachusetts did not introduce bills changing the management of public lands in Utah. Today it is common. Many courtesies of civil government have disappeared in Washington, but this one is especially disturbing to Westerners, who can’t just get out the shotgun to defend their turf. This is not the movies.

The deference shown congressmen from the area affected by a bill was more than just old-fashioned courtesy. People who lived in the area were considered most knowledgeable about what would and would not work there, and it was assumed that they had the public interest at heart. It was not sentimentality; it was common sense.

I remember during a 1991 Club 20 trip to Washington, a very spirited conversation with a Senate staffer from Rhode Island, whose boss was pushing legislation to designate wilderness areas in Colorado. We failed miserably to convince him that Rhode Island congressmen should leave Colorado land management to Coloradans. These lands belong to all the people, he rightly pointed out. We also failed to persuade him that most of the locals had a different viewpoint. He maintained that the people who live there are a minority, which is also true. We said people who lived there knew more about those lands, but that offended him. He said he worked for constituents in Rhode Island and it was not his job to care what the people in the West thought. As a last resort, we tried to explain the importance of multiple use, upon which businesses and communities depended, and which the proposed wilderness legislation would effectively ban. He countered with a glowing description of the area as one of the last great places in America, so I asked the question many Westerners often wonder, “Have you ever been there?” He had not, but I will never forget his response: “We don’t have to visit the place to care about it. For many of us,” he said, “it’s enough just to know it’s there.”

That staffer is long gone, but not his arrogance. Last month Rhode Island’s current Senator, Sheldon Whitehouse, led a partisan coalition of Eastern Senators, along with retiring Senators Barbara Boxer (CA) and Harry Reid (NV), to introduce the Northern Rockies Ecosystem Protection Act. A similar House bill has been introduced annually for 24 years, without a hearing. That’s because no Member from the Northern Rockies supports it. The bill would designate as wilderness more than 23 million acres of Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, Oregon and Washington, and also designate 1,800-miles of rivers and streams as Wild and Scenic.

Besides Whitehouse, Boxer, and Reid, the sponsors include Senators from Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Hampshire, and New York. Keep in mind that Rhode Island has no National Forests or Wilderness Areas, but it does have about 5,000 acres of federal land, mostly in small wildlife refuges. Whitehouse has made no effort to designate those as wilderness. His entire state would fit inside several Wilderness Areas we already have in the Rockies.

If these Senators care so much about permanent protection for federal lands that otherwise enjoy many different public uses, perhaps they should work on wilderness designations for the 300,000 acres of forest lands in Illinois, the 61,000 acres of federal land in Massachusetts, or 179,000 acres in New Jersey. New York also has a 16,000-acre National Forest that seems like a good candidate (it is beautiful, after all).

The Rocky Mountain states, on the other hand, already have substantial congressionally-designated Wilderness Areas: 4.7 million acres in Idaho, 3 million in Wyoming, 3.5 million in Montana, 2.4 million Oregon, and 4.4 million in Washington. Those areas and others were designated with direct involvement by a generation of Senators from the Rockies: Bill Armstrong, Hank Brown, Tim Wirth, Wayne Allard, Alan Simpson, Malcolm Wallop, Max Baucus, John Melcher, Barry Goldwater, Dennis Deconcini, Pete Domenici, Orrin Hatch, Jake Garn, Robert Bennett, Paul Laxalt, Dirk Kempthorne, Jim McClure, Steve Symms, and others.

There are already over 100 million acres of designated Wilderness Areas. And not one single Senator of either party from any of the impacted States thinks there is a crisis requiring this new Northern Rockies wilderness bill. Instead, they are unanimously demanding a return of the traditional courtesy, like Clint Eastwood thundering from his front porch, “get off my lawn!”

(A version of this column originally appeared in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel June 17, 2016)

Comments on this entry are closed.